No need to fear the giant flying electric joro spider

Contact

Jon Zawislak

Assistant Professor, Apiculture and Urban Entomology

Phone: 501-671-2222

Email: jzawislak@uada.edu

Office:

Crawley Warren Bldg, Room 6

2601 N. Young Ave

Fayetteville, AR 72704

Austin Jones

Instructor and Director of Undergraduate Education,

Entomology and Plant Pathology

Phone: 479-575-2445

Email: akj003@uark.edu

Office:

University of Arkansas

Dale Bumpers College of

Agricultural, Food, and Life Sciences

Entomology and Plant Pathology

PTSC 217

University of Arkansas

Fayetteville, AR 72701

No need to fear the giant flying electric joro spider

Austin Jones, Instructor and Director of Undergraduate Education

Jon Zawislak, Assistant Professor – Apiculture and Urban Entomology

Sensational headlines are popping up across the country about the latest trending species introduced to the United States, the joro spider (Trichonephila clavata). Eye-catching articles highlight these spiders as being giant, venomous, and if that was not enough to pique America’s arachnophobic interests, they are also tagging these spiders as “flying.” However, in practice these sensationalized claims, just like the spiders themselves, do not have wings, and as with much of the news today, there is less to worry about than headlines suggest.

What are joro spiders?

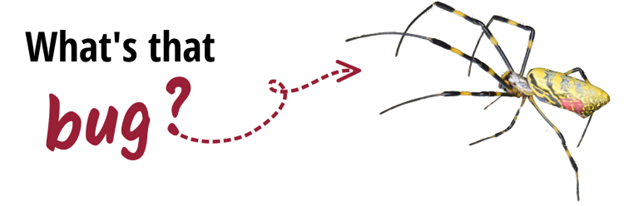

Joro spider (Trichonephila clavata)

photo © Daniel Ramirez (CC BY 2.0 flickr.com)

Joro spiders are an impressive looking species of orb-weaving spider, with females exhibiting striking colored markings on their body and legs. Orb-weavers create large angular-yet-circular webs, often depicted in everything from children’s books to low budget horror films. The spider family Araneidae (A-rain-E-ah-day) contains about 3500 species of orb-weavers, with more than 150 species native to the U.S. The closest native relative of the joro spider is very similar in overall body shape, habits, and size, and is known as the golden orb-weaver (Trichonephila clavipes). Golden orb-weavers have actually been farmed for silk production in some instances, and females can be distinguished from joros by coloration that is less striking, and presence of obvious tufts of hair on three of their four pairs of legs (for those brave enough to get a closer look). Other iconic native orb-weavers and friends of the gardener are the familiar garden spiders (Argiope aurantia and A. trifasciata). These could be mistakenly identified as joros by the public as they are also large and strikingly colored with yellow, black and white markings. Garden spider females can actually get larger than joros and can be identified by their web, which contains a visible zig-zag pattern that runs through the center of the web. This structure is called a stabilimentum. This distinctive feature may serve to help birds and other large creatures see and avoid the web, or it may reflect UV light that attracts prey, or perhaps both.

Where are joro spiders found?

Joro spiders are native to Japan and many other parts of Asia. They have not yet been reliably reported in Arkansas at the time of this article. However, a lone observation from Bartlesville, Oklahoma, was recorded in the iNaturalist database, with the user mentioning that it was likely transported during a recent road trip to Athens, Georgia (so it may well have passed through the Natural State). Athens, coincidentally, is very close to where the joro was first documented in the U.S. in 2014, and a known hot spot of joro sightings. This highlights the ability of these spiders to hitchhike in goods and on vehicles to new areas. With much of the Eastern U.S. habitable to this species, it is likely a matter of time before joro spiders become more widespread via human-assisted relocation, both adults and their egg sacs.

Are joro spiders giant, and can they fly?

Of course the term giant is relative, but many would use the term to describe the mature female joros, which can reach a body length of about 1 1/4 inches, not including legs. Their leg span can reach as far as 4 inches. So, while not likely to pick up and carry off your pets, they are quite a bit larger than jumping spiders or black widows for instance. Females still fall far short of tarantula size and males would be overlooked by most people, as they lack the striking coloration of the females and only reach a little over ¼ inch in body length. And, despite rumors to the contrary, these spider cannot technically fly. Like any other spider, adults will never be airborne unless they have fallen from a height or been picked up by the wind. However, baby joro spiders do perform an activity known as ballooning, which is a common method or dispersal for many spider species. The tiny and very lightweight spiderlings push out some web into the breeze and catch it much like a miniature kite. Where these ballooning spiders land is generally up to the winds of fate instead of targeted destinations. Interestingly, it has also been shown that some spiders can not only balloon on wind currents, but also using electromagnetic fields. So, could a joro spider land in your yard from the sky? Sure, but you would not likely even notice it. Each spring overwintering egg sacs will spill forth with tiny ballooning daredevils that, if successful, will become mature by fall and will perish in late autumn or winter.

Are joro spiders venomous or dangerous?

Of more than 40,000 known species of spiders on earth, only one is known to feed solely on plants, the rest are predators, which will sometimes scavenge, feeding on dead arthropods. Of these predators, only one single family is known to not be venomous – the uloborid spiders – which vomit on their prey instead of injecting venom and consist of more than 300 species globally. For practical purposes one could say that “all” spiders are predators and that “all” spiders are venomous and be right “all” the time. So, yes, joro spiders are venomous, but their venom is of no more danger or potency than the many other native spiders which are nearly all of little concern. In North America the widows (Latrodectus) and recluses (Loxosceles) are the only two spider genera documented to have medically important bites and between them consist of 10 species. Of these, the brown widow (Latrodectus geometricus) and the Mediterranean recluse (Loxosceles rufescens) were also introduced into the U.S. accidently.

As populations of joro spiders spread, they will be competing with native species for prey, and may displace or outcompete some local spiders, potentially leading to conservation issues. Should these spiders outcompete native species and reach large populations due to a lack of natural predators or disease, it could also impact imperiled pollinator insect groups such as butterflies and bees, but these situations have not yet manifested in the areas where joros are already observed. On the whole, having a joro or two in your yard helping to control other pestiferous species could be seen as a benefit. After all, spiders are our friends when it comes to eating insects, and if joro spiders lived up to the hype of being giant, flying, venomous homewreckers, gun control laws would likely be less hotly debated.

Summary

- Are joro spiders giant? They are large for web-building spiders, but not near the size of a tarantula.

- Can joro spiders fly? Technically no, but they can balloon. Only juveniles can become airborne and do so by riding the wind with kites made of spider web when they are still quite small.

- Are joro spiders venomous? Yes, but so is nearly every spider, and their venom is not medically important.

- Are joro spiders dangerous? No, they are not aggressive and would only bite if provoked. They may pose some threat to natural spider populations and ecosystem integrity.