Arkansas Extension Small Ruminants

Contact

Dr. Dan Quadros

Asst. Professor - Small Ruminants

Phone: 501-425-4657

Fax: 501-671-2185

Email: dquadros@uada.edu

University of Arkansas System

Division of Agriculture

Cooperative Extension Service

2301 S. University Ave.

Little Rock, AR 72204

Nutritional Strategies for Small Ruminant Gastrointestinal Nematode (GIN) Management

By Dr. Dan Quadros UA Division of Agriculture Small Ruminant Specialist and Dr. Joan Burke USDA-ARS Dale Bumpers Research Animal Scientist

Managing gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) is a critical challenge for small ruminant producers. These parasites impact health, productivity, and overall farm profitability. It also creates welfare concerns and severe economic losses related to reduced productivity, cost of treatment, and, eventually, mortality.

While traditional approaches often rely on chemical dewormers, integrating nutritional strategies into management plans offers a sustainable and effective alternative.

Devastating Parasites in Small Ruminants

The most economically significant GIN in small ruminants belong to the order Strongylida and family Trichostrongylidae, inhabiting different parts of the digestive tract.

Key species include:

- barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus)

- brown stomach worm (Teladorsagia circumcincta)

- bankrupt worm (Trichostrongylus colubriformis)

- nodular worm (Oesophagostomum columbianum)

which are commonly linked to parasitic gastroenteritis in the abomasum, small intestine, and large intestine.

The barber pole worm, the most common and pathogenic gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) in small ruminants in tropical and subtropical regions, causes substantial protein losses due to its blood-feeding habit, primarily linked to anemia (see Figure 1). These parasites damage abomasal tissue, resulting in blood loss, anemia, and depletion of essential minerals like phosphorus, calcium, and copper (Coop and Sykes, 2002; Hoste et al., 2016). Additionally, infections redirect nutrients from growth and reproduction to immune responses and tissue repair, compounding their negative effects, particularly during pregnancy and lactation.

Figure 1. Goat with severe anemia caused by barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus). The pale to white conjunctiva, weakness, lethargy, and sudden death are clinical signs of hemonchosis.

How do parasites spread in small ruminants?

During the parasitic phase, adult worms live in the animals. Their eggs are shed in the animal’s feces, contaminating the pastures. The animal infection occurs via ingestion of larvae present in contaminated forage.

How do parasites harm small ruminants?

GIN infections impair nutrition and metabolism, reducing voluntary feed intake, lowering feed efficiency, and altering nutrient utilization (Hoste et al., 2016). Even mild infections can decrease feed intake by 10% to 30%, limiting nutrient absorption and affecting performance (Coop and Sykes, 2002).

Parasitized animals experience reduced enzymatic function, impaired digestion, and decreased nutrient absorption in the small intestine. Nutrients are diverted from growth and reproduction to repair and immune responses, prioritizing tissue maintenance over other functions. During pregnancy and lactation, nutrient allocation to reproduction takes precedence over immunity, leading to a peri-parturient rise in parasitic output (Coop and Sykes, 2002).

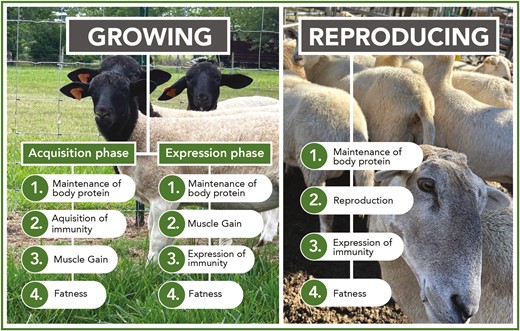

The allocation of absorbed nutrients varies according to the order of priority, depending on the physiological stage of the animals, such as growth and reproduction (Coop and Kyriazakis, 1999). In all physiological stages, maintenance of body protein, including repair, replacement, and reaction to damaged or lost tissue, is the number one priority (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Possible prioritization of body functions (1 highest to 4 lowest) for a growing or reproducing animal partitioning scarce food resources. For a naive animal without prior gastrointestinal nematode challenge experience, immunity acquisition is separate from its expression. Maintenance of body protein involves repair, replacement, and reacting to tissue damage. Source: Adapted from Coop and Kyriazakis (1999).

Nutrition Plays a Key Role in Managing Parasites

Targeted nutritional approaches can improve resistance and resilience to GIN infections, supporting animal health and performance.

Use these key nutriton strategies:

1. Pasture Management and Complementary Forages

Optimizing pasture management is crucial in reducing GIN infection risk.

- Rotational Grazing: Controls grazing intervals and stocking rates, reducing larval ingestion and improving forage quality (Glennon, 2017; Burke and Miller, 2020).

- Co-Grazing: Using cattle or horses alongside small ruminants limits cross-infection (Bricarello et al., 2023).

- Annual Forages: Crops like pearl millet, oats, rye, and wheat not only provide high-quality nutrition but also disrupt parasite life cycles (Glennon, 2017).

For goats, incorporating browsing systems such as silvopasture or woodlot vegetation is highly effective. Browsing naturally lowers parasite exposure compared to grazing sheep, while providing nutrient-rich forage (Hoste et al., 2008).

2. Protein and Energy Supplementation

Protein-rich diets strengthen immune responses, helping animals combat GIN infections. Energy supplementation also supports resilience and overall productivity. Studies show that protein supplementation reduces fecal egg counts and worm burdens.

3. Mineral and Vitamin Supplementation

Adequate levels of minerals such as copper and zinc are essential for enhancing resistance to GIN. Copper oxide wire particles (COWP) have proven effective in managing barber pole worm infections, reducing parasite burdens, and boosting dewormer efficacy.

4. Plant Secondary Compounds

Plants containing condensed tannins, such as certain legumes and shrubs, aid in managing GIN while improving feed efficiency. These compounds reduce worm burdens, enhance nutrient absorption, and lower methane emissions, contributing to a more sustainable farming system.

Plants rich in condensed tannins with demonstrated activity against GIN in sheep and goats include:

- sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata)

- sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia)

- sulla (Hedysarum coronarium)

- black wattle (Acacia mearnsii)

- big trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus)

- birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), among others

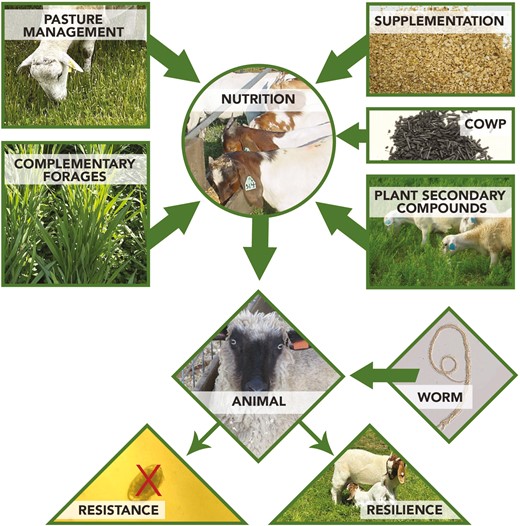

These strategies in a small ruminant IPM (integrated pest management) program should be seen in a holistic approach, in which its effects on host-parasite interaction are not isolated (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Nutritional strategies for managing gastrointestinal nematodes in small ruminants. These include pasture management (species, environment, grazing system), complementary forages (grains, hay, silage, byproducts), supplementation (protein, energy, minerals, vitamins), copper oxide wire particles (COWP; dose, frequency), and planting secondary compounds (legumes, herbs, shrubs). Nutrition affects animal response (age, breed, resistance, production level, physiological stage) to worms, increasing resistance (decreasing fecal egg counts) and resilience (hematocrit, performance).

Why Nutritional Strategies Matter

Integrating nutritional approaches into gastrointestinal nematode management plans benefits both animal and farm health.

These strategies:

- Reduce reliance on chemical dewormers, slowing parasite resistance development.

- Enhance animal productivity and overall resistance and resilience.

- Promote environmentally friendly and cost-effective farming practices.

By prioritizing nutrition, producers can tackle the challenges of GIN sustainably, ensuring healthier animals and more profitable operations.

Key Takeaways

- Effective pasture management minimizes gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) risks while improving forage quality for small ruminants.

- Protein supplementation boosts resistance and resilience to GIN infections.

- Copper oxide wire particles (COWP) help combat barber pole worm infections and enhance dewormer effectiveness.

- Condensed tannin-rich plants support sustainable parasite control and improve feed efficiency.

This blog post was adapted from Quadros, D. and Burke, J., 2024. Nutritional strategies for small ruminant gastrointestinal nematode management. Animal Frontiers: the Review Magazine of Animal Agriculture, 14(5), p.5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfae019

For more detailed information, read the entire journal article here.