Arkansas Extension Small Ruminants Blog

Contact

Dr. Dan Quadros

Asst. Professor - Small Ruminants

Phone: 501-425-4657

Fax: 501-671-2185

Email: dquadros@uada.edu

University of Arkansas System

Division of Agriculture

Cooperative Extension Service

2301 S. University Ave.

Little Rock, AR 72204

Alleviating Heat Stress in Small Ruminants

By Dr. Dan Quadros, UADA Small Ruminants Specialist

6/29/23

With the dangerous heat wave hitting Arkansas right now, producers must take measures to combat heat stress in sheep and goats.

On average, heat stress is experienced in sheep and goats when the temperature humidity index (THI) is at moderate (82 to <84 °F), severe (84 to < 86 °F) and extreme (≥86 °F) levels.

Goats tend to tolerate heat better than sheep. Goats with loose skin and floppy ears may be more heat tolerant than other goats. Dark-colored animals are more susceptible to heat stress, while light-colored animals may be prone to sunburn. Smaller animals are more tolerant than larger ones. Females usually handle heat better than males.

The heat is especially hard on fat animals. Hair sheep can tolerate heat stress better than most wool sheep, but some wool animals from hot environments can tolerate heat stress like hair sheep. However, hair breeds that have undergone selection are less tolerant. Horned animals dissipate heat better than polled (or disbudded) animals. Young animals are more susceptible to heat stress than older animals, while geriatric animals are vulnerable. Any animal with a poor nutritional status or compromised immunity is more susceptible to extreme temperatures.

Should I shear my sheep and goats in extreme heat?

Sheep and goats should not be sheared in extreme heat. Wool protects sheep from extreme heat as well as extreme cold. A thick fleece is mostly immune to temperature changes due to its insulating properties. If sheared in the spring, sheep will have adequate wool growth to keep them cool in the summer (and avoid sunburning) and a full wool coat in the winter to keep them warm.

What are the signs of a heat-stressed goat?

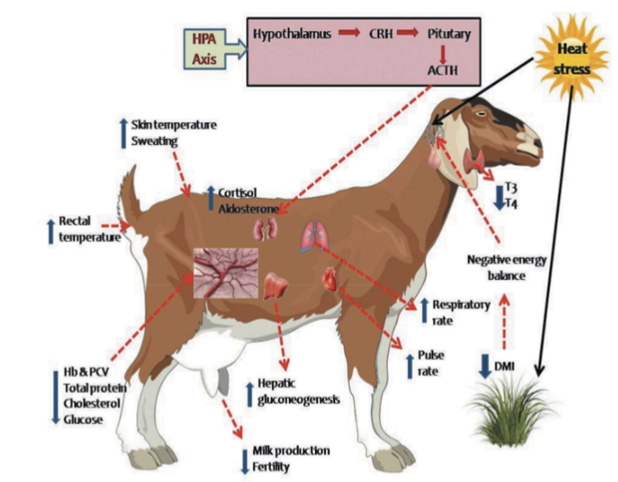

A heat-stressed sheep or goat will sweat, open-mouth pant and will experience increases in respiration rate (breaths/minute; normal respiration rates range from 15 to 38 breaths/min) and rectal temperature (normal body temperature is 101.5 to 103.5 °F). This creates a cascading effect on biological functions, including depressed feed intake, feed efficiency and even affecting water, protein, energy and mineral balances, which leads to overall reduced performance (Figure 1).

Source: Gupta and Mondal (2021)

Figure 1. Negative impacts of heat stress on small ruminants

How can I alleviate heat stress?

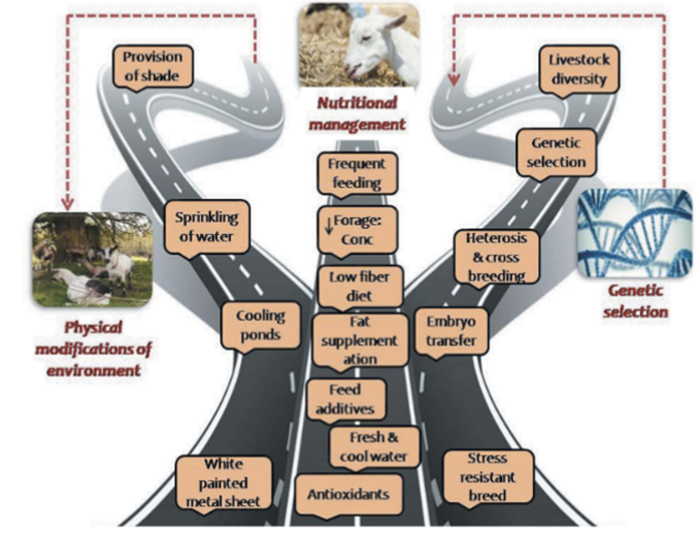

The strategies to alleviate heat stress on sheep and goats require a multidisciplinary approach. The amelioration strategies can be broadly grouped into three categories:

- physical modifications of environment

- nutritional management

- genetic development of thermotolerance breeds (Figure 2)

Source: Modified from Sejian et al. (2018) by Gupta and Mondal (2021)

Relevant amelioration strategies to counteract heat stress in small ruminants.

Provide Extra Water

Providing plenty of clean, cool, and fresh water is paramount to preventing heat stress in livestock. During periods of extended heat and humidity, it may be necessary to provide extra water and change water out more often. On average, a sheep or goat will drink 1 to 2 gallons of water per day. Lactating females will drink even more water.

Provide Shade

Access to shade is another important aspect of managing livestock during hot weather. Livestock shelters does not need to be complicated or elaborate. Mature trees provide excellent shade (and shelter) and are usually a low-cost option.

If natural shelter is not available, many sheep and goat producers use quonset huts, plastic calf hutches, polydomes, and/or carports to provide shelter for grazing animals. Simple shade structures can be constructed from shade cloth, mesh fabric, tarps, canvas, or sheet metal. Movable shade structures are suitable for intensive rotational grazing systems.

All livestock should be able to lie down in the shade structure or area at the same time. Lying down in a cool spot provides additional relief from the heat.

Install Cooling Systems

When livestock are housed indoors, install an evaporative cooling system with water in the form of fog, mist or sprinkling with natural or forced air movement.

Manage Nutrition

Ration modifications can greatly help in reducing the negative impacts of heat stress. During summer, the feeding should be done during the cooler periods of the day as it encourages them to maintain their normal feed intake. Also, feeding at more frequent intervals is beneficial to minimize the diurnal fluctuation in ruminal metabolites and thus, increase feed utilization efficiency in the rumen. Decreasing the forage to concentrate ratio can result in more digestible rations that may be consumed in greater amounts.

Feed additives have been proposed to offset the consequence of heat stress. For example, supplementation of live yeast, vitamin C and E.

Use Genetic Selection

Genetic selection is an important aspect to alleviate the impact of heat stress. Studies that enable the identification and quantification of biomarkers for heat stress can help to develop agroecological zone-specific breeds.

Key Takeaways:

- Provide extra fresh water and refresh more frequently

- Provide shade

- Change diets and feeding practices

- Avoid animal work during peak heat times (10 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.)

- Ensure adequate ventilation and air movement for animals housed indoors

Bibliography

- Froehlich, K. Heat stress in small ruminants. South Dakota State University. 2023. https://extension.sdstate.edu/heat-stress-small-ruminants#:~:text=Alleviating%20Heat%20Stress&text=When%20possible%2C%20provide%20shade%20during,movement%20to%20animals%20housed%20indoors.

- Gupta, M; Mondal, T. (2021) Heat stress and thermoregulatory responses of goats: a review, Biological Rhythm Research, 52:3, 407-433, DOI: 10.1080/09291016.2019.1603692

- Maryland Small Ruminant page. Heat stress in sheep and goats. https://www.sheepandgoat.com/heatstress#:~:text=Sheep%20and%20goats%20tend%20to,training%20and%20trialing%20herding%20dogs.

- McManus, Concepta M., et al. Heat stress effects on sheep: Are hair sheep more heat resistant? Theriogenology 155 (2020): 157-167.

- Sejian, V., et al. (2021). Heat stress and goat welfare: Adaptation and production considerations. Animals, 11: 1021.