Entomologist wants to know if invasive mosquitoes, native biting midges make good neighbors

By Fred Miller

U of A System Division of Agriculture

@AgNews479

Fast facts

- Invasive Asian tiger mosquitoes sometimes compete with natives for habitat

- Entomologist investigates interaction of invasive mosquitoes and native biting midges

- Competition causes stress and may increase risk of disease transmission to humans

(1,061 words)

Related PHOTOS: https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjzU9Ss

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Robert Frost derided the idea that good fences make good neighbors. But Emily McDermott is investigating what hinders neighborliness among bloodsuckers.

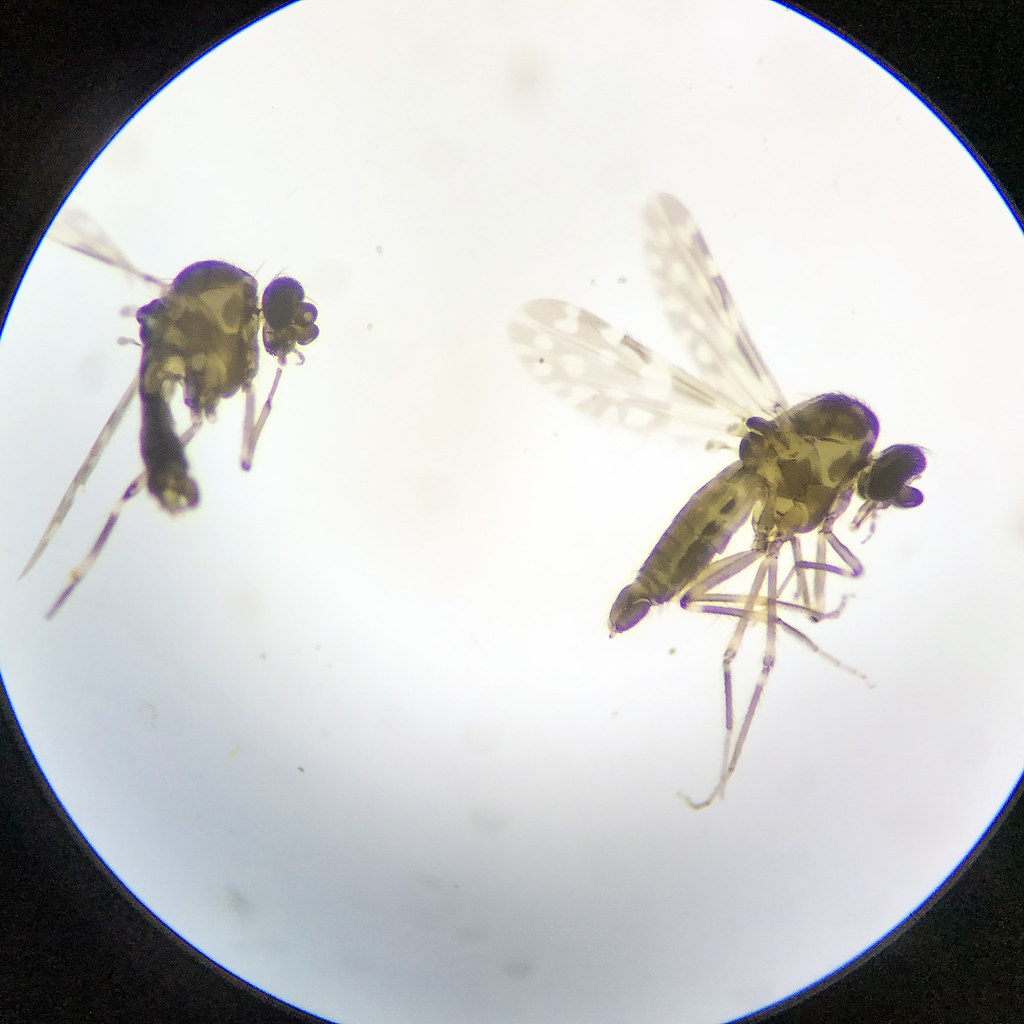

McDermott, assistant professor of entomology for the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, wanted to find out if invasive Asian tiger mosquitoes and native biting midges — commonly called “noseeums” — were inclined to share habitat resources.

The answer seems to be “no,” but the reasons are unclear. McDermott plans to investigate the matter further this summer.

The Agricultural Experiment Station is the research arm of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. McDermott also has a teaching appointment in the Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences at the University of Arkansas.

Resource preferences

The Asian tiger mosquito — Aedes albopictus — is native to tropical and subtropical climates. McDermott said it arrived in the United States about 30 years ago and now extends as far north as New York. The pest is a known carrier of disease pathogens, including Zika and Dengue viruses.

McDermott said existing research has shown that the Asian tiger mosquito can out-compete native mosquitoes that prefer the same habitats for laying eggs. The Asian tiger mosquito prefers artificial habitats like old tires, clogged rain gutters or any objects that can hold standing water. But in rural areas where artificial water caches are rare, it will use natural habitats like hollows in tree limbs or roots.

Another common native mosquito in Arkansas, an Aedes species often called the eastern tree hole mosquito, prefers natural habitats, McDermott said. The two species can co-exist in urban areas because of their different habitat preferences. But in rural areas, the more aggressive Asian tiger mosquito tends to out-compete the native Aedes mosquito for those small natural pools.

Good neighbors — bad neighbors

McDermott wanted to find out if the Asian tiger mosquito was having any impact on the larvae of native biting midges, another kind of bloodsucker that breeds in standing water.

Native biting midges include several species, often called “noseeums,” sometimes confused with black flies. “Noseeums are hard to see,” McDermott said. “If you can see what’s biting you, that’s probably a black fly. If not, it’s a biting midge.”

Being bitten by noseeums is no fun, but the good news is that the midges don’t transmit human diseases in the U.S.

To see if the Asian tiger mosquito was sharing water resources with biting midges, McDermott and research associate Cierra Briggs collected water samples from natural and artificial container habitats in search of mosquito and midge larvae.

They found the midges frequently shared pools with native mosquitoes but only rarely with the invasive Asian tiger mosquito.

“This makes sense,” McDermott said. “Native midges and native mosquitoes evolved together and developed the ability to share resources without causing negative effects to each other.”

The midges, like the native mosquitoes, prefer natural habitats. Finding fewer midges with Asian tiger mosquitoes might be attributed to their different preferences in where they lay their eggs. But McDermott said this can’t entirely explain their separation.

Trial by water

This summer, McDermott said she and Briggs will conduct experiments to study the interactions of Asian tiger mosquitoes and native biting midges. They will establish container habitats and allow the midges to colonize them. Then they will introduce Asian tiger mosquito larvae to some of those containers and restrict the rest to the midges.

“We’ll monitor the containers to see if the invasive mosquitoes out-compete the native midges,” McDermott said.

If they see that the midge larvae decline or disappear from the containers containing mosquito larvae, especially if the midges survive in the control containers, the evidence will indicate a negative interaction. Then the question becomes how the mosquitoes eliminate the midges.

“The mosquitoes are either eating all the existing food and starving the midge larvae, or predation is occurring,” McDermott said. The midges are becoming food.

Why do we care

Mosquitoes can transmit diseases to humans and animals after first becoming infected with the pathogens, McDermott said. Healthy adult mosquitoes’ immune systems can ward off the pathogens, making transmission less likely.

Competition for resources can stress mosquito larvae. Researchers are uncertain whether this reduces the larvae population, but it can affect the health of adults.

“Laboratory research indicates that stressed larvae develop into less fit adult mosquitoes that may not be able to shrug off an infection,” McDermott said. “If there are a larger number of infected mosquitoes, it follows that there is a higher risk of disease transmission.”

Knowing whether the Asian tiger mosquitoes are sharing their larvae habitats with midges or competing for the resources can indicate whether the mosquitoes present a greater risk of spreading diseases to humans, McDermott said.

Self-protection

Different species of mosquitoes are active at different times of day and night, McDermott said. The tree hole mosquito bites at dusk and dawn but will also bite during the day in wooded areas. Another native, the Anopheles mosquito, is common in eastern Arkansas and is a night feeder, biting almost all night.

Asian tiger mosquitoes, which have become more common in northwest Arkansas, tend to begin feeding mid to late afternoon and continue until shortly after sunset.

McDermott said that the most effective way to reduce mosquitoes on your property is to reduce available habitats.

“Remove standing water,” she said. Drill holes in old tires, corrugated downspout extenders or other objects that might hold rainwater for several days. It’s also a good idea to clean gutters and cover rain barrels with lids designed to keep mosquitoes out.

Adult female mosquitoes lay eggs in water soon after a blood meal. The eggs hatch larvae, which change to pupae before emerging as adults. The time in the water varies based on water temperature and mosquito species, but McDermott said five days is a good rule of thumb. She recommends changing the water in birdbaths and water bowls for pets at least every three days.

“Anything you can do to avoid standing water will help,” McDermott said. “Ideally, everybody should take these steps.”

For decorative water fountains or ponds, McDermott recommends using mosquito dunks. These small donut-shaped control products float in the water and slowly dissolve, releasing a bacterium that is toxic to all mosquito species. Each dunk lasts about 30 days, and the products are widely available.

Detailed information about mosquito control is available online from the Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service: https://bit.ly/3aKvqsf.

To learn more about Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website: https://aaes.uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @ArkAgResearch. To learn about Extension Programs in Arkansas, contact your local Cooperative Extension Service agent or visit https://uaex.uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @AR_Extension.

To learn more about the Division of Agriculture, visit https://uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @AgInArk.

About the Division of Agriculture

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation’s historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

Pursuant to 7 CFR § 15.3, the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs and services (including employment) without regard to race, color, sex, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, sexual preference, pregnancy or any other legally protected status, and is an equal opportunity institution.

Media Contact: Fred Miller

U of A System Division of Agriculture

Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station

(479) 575-5647

fmiller@uark.edu

Related Links