Sept. 19, 2022

Retired entomologist helped pioneer IPM; brought bugs to the people

By Fred Miller

U of A System Division of Agriculture

@AgNews479

Fast facts

- Pioneered biological control of cotton aphids

- Originated the University of Arkansas Insect Festival

- Dedicated career to research, outreach and teaching

(1,742 words)

Related PHOTOS: https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjA74ai

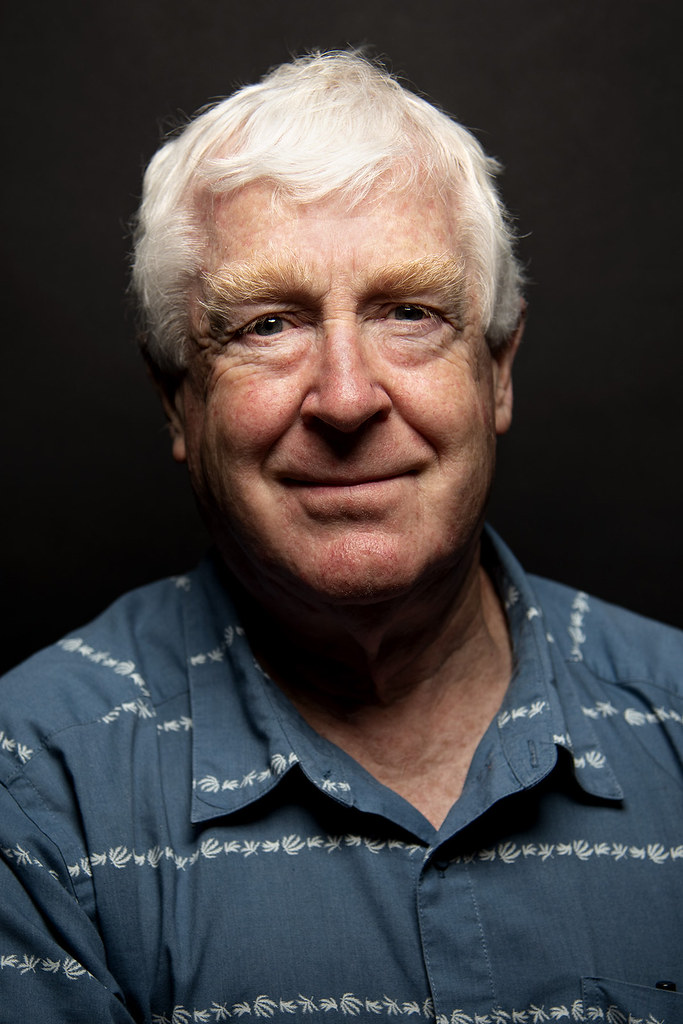

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Don Steinkraus joined the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station in 1989 and launched a successful career in integrated pest management research in row crops. He also became a window into the captivating world of insects for generations of students and Arkansas residents of all ages.

Steinkraus retired in June 2022. But he’s not yet done with the tiny, multi-legged intrigues of arthropods.

The Agricultural Experiment Station is the research arm of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. Steinkraus also had a teaching appointment in Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences at the University of Arkansas.

“When I think of Don, I think ‘entomologist,” said Ken Korth, head of the department of entomology and plant pathology for the Division of Agriculture and Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences at the U of A.

“His long and productive career is exemplary for what a faculty member in the land-grant system should aspire to,” Korth said.

After earning his Bachelor of Science degree at Cornell University, Steinkraus earned a Master of Science degree in mycology (the study of fungi) at the University of Connecticut. He returned to Cornell to complete his doctorate in entomology and worked as a post-doctoral researcher in veterinary entomology.

Research

When Steinkraus was looking for a project to get his research started, he got a boost from Phil Tugwell, a veteran cotton entomologist known for being generous with information, especially for young faculty trying to carve out their niches.

Tugwell died in October 2021. His obituary can be found at https://aaes.uada.edu/news/phil-tugwell-2/.

“Phil told me, ‘Don, something is killing cotton aphids.’ At that time, aphids were an important pest in cotton,” Steinkraus said. “It was just his observation, but he thought it might be something I ought to look into.”

Aphids excrete a substance called “honeydew” that supports the growth of saprophytic fungi — fungi called “sooty molds” that damage cotton leaves and make “sticky” cotton. Tugwell thought a fungus might be behind the dying aphids. He showed dead aphids to some plant pathologists who were working on fungal plant pathogens as potential weed biocontrol. “They couldn’t figure it out,” Steinkraus said.

Steinkraus examined the samples and figured out that it was a fungus known as Neozygites fresenii, a species from a fungal group that specializes in infecting arthropods.

“The reason the plant pathologists couldn’t figure it out,” Steinkraus said, “was that the fungus was an insect pathogen that they weren’t familiar with.

“If Phil Tugwell hadn’t made his observation and pointed me to it, I might never have looked at it,” he said. “Good science always begins with astute observation.”

After Steinkraus presented his paper on this fungus at a scientific conference, a research director from Cotton Incorporated came up to him and said the nonprofit company that supports cotton research wanted to fund his program. “And they did fund it for 20 years,” Steinkraus said.

The funding allowed him to buy precision microscopes and other lab and field equipment and to hire research assistants. With that support and grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Steinkraus began looking for a way to use N. fresenii as a biological control for cotton aphids.

“We did a lot of research,” Steinkraus said. But his experiments could not reveal how to apply the fungus as a biological control.

“It’s very host specific,” he said. “We couldn’t grow it on artificial growth media.”

Instead, Steinkraus applied his knowledge of epizootiology — epidemiology of animals — and developed a way to plot the spread of the fungal infections in cotton aphid populations based on sampling and diagnosis. That allowed his research team to predict when aphid populations would begin to decline and determine if a population crash would occur before the pests could significantly damage cotton plants.

“We could inform farmers whether or not the pathogen was going to kill the cotton aphids before they could do any harm,” Steinkraus said. “Knowing when you had to spray and when you didn’t meant Arkansas cotton growers saved millions of dollars a year when you didn’t need pesticide applications.”

The Entomological Society of America awarded Steinkraus its Excellence in Integrated Pest Management award in 2000 for his research on cotton aphid biocontrol.

“Dr. Steinkraus’ career has been exceptional for his contributions in several areas of entomology, but especially adding to the understanding and use of biocontrol of insects,” Korth said. “He has published multiple research studies on fungi and other pathogens that infect arthropods and explored their potential as agents to control pests. His work is widely known by colleagues and in the popular press.”

“The cotton aphid research was a real collaborative effort,” Steinkraus said. “It was my bread and butter for 20 years.”

Cotton Incorporated felt like they got their money’s worth from his research. Steinkraus said a former president of the nonprofit told him his work gave them the biggest bang for their buck. “He told me my relatively inexpensive research provided enormous benefit to cotton farmers.”

Teaching

“I was hired as research faculty, with 80 percent of my appointment in the experiment station,” Steinkraus said. “Only 10 percent of my appointment was for teaching in Bumpers College. But I did a lot more than 10 percent teaching.”

“Don is a skilled teacher and researcher, and he has always emphasized understanding natural systems and consideration of practical applications of his work,” Korth said.

The first class he was assigned to teach was Insect Morphology — about the anatomy of insects.

“It was a very difficult course,” Steinkraus said. “Difficult to teach, difficult to learn. But I grew to love it.”

He taught Insect Morphology for more than 30 years and said he would like to write a book on it.

Along the way, he began keeping honeybees as a hobby. The department of entomology had a course on beekeeping taught by Lloyd Warren. When Warren retired, Gerald Wallace started teaching the class. And when Wallace retired, Steinkraus took it on. He taught the course for 20 years. It was a natural for a hobbyist beekeeper.

“It was a lot of fun to teach,” Steinkraus said. “It was very hands-on. I had students put bees into colonies, collect honey and do other beekeeping activities.”

Jon Zawislak, assistant professor of apiculture and urban entomology for the Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service, met Steinkraus when he applied for a summer job.

“It was Dr. Steinkraus who first introduced me to entomology,” Zawislak said. “We got along, and the work was interesting, and after the summer work was finished, he asked if I 'd like to stay on and help him with some other projects he was doing. That summer job lasted about eight years, during which we worked on a number of different areas of research.”

In 2007, Steinkraus and Zawislak removed more than 100,000 bees from the fifth floor of Old Main on the U of A campus. Construction workers found the bees during a renovation project, and the colony held up the work.

They moved the bees to beekeeping hives on the Division of Agriculture’s Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center, located about two miles north of the U of A campus.

It was the bees that really hooked Zawislak. He studied bee health for his master’s degree research under Steinkraus’ advising. This interest led to the creation of his position as a honeybee specialist for the Cooperative Extension Service.

“So, because of a random job that I applied for many years ago, Dr. Steinkraus really steered me into a rewarding career I probably never would have considered,” Zawislak said. “He has been a friend and mentor to me for a long time.”

After taking over the beekeeping class, Steinkraus later took over Intro to Entomology, a course for non-science majors previously taught by his retired colleague Max Meisch.

“Max dreamed of a science core course for non-science majors,” Steinkraus said. The class teaches the highlights of entomology.

After teaching it for two years, Steinkraus proposed that the university accomplish Meisch’s dream. “That was done,” he said. “Enrollment jumped from 40 students to 120 in the first year after it became a core course. It’s still an extremely popular course. It fills up with 120 students every year.

“It gives non-science students an appreciation of science,” he said. “And it’s fun.”

Outreach

Korth said Steinkraus had a natural talent for sharing his passion for the insect world with people outside the discipline.

“Among his many skills, Don is a gifted communicator of the science, applications, and beauty in entomology,” Korth said. “He is routinely our go-to person for interviews with all media outlets.

“He has been especially active statewide, regularly presenting with Master Gardener and Master Naturalist groups in Arkansas,” Korth said. “Whether it is Emerald Ash Borers or Asian giant hornets, Don can explain to a general audience in educational and entertaining ways.”

Steinkraus wanted to share the insect world with all age groups. In 1993, he submitted a proposal to organize an insect festival.

“We got a little money from the university,” Steinkraus said. “We held the first two festivals in Giffels Auditorium, in Old Main. It was an amazing success, and Giffels was too small to host it.”

Today, the University of Arkansas Insect Festival is held in the Pauline Whitaker Animal Science Center on the Division of Agriculture’s Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

“Every one of the festivals has been a big success,” Steinkraus said. “We get about 3,000 people each year. The festival brings together entomologists and plant pathologists from all over the state.

“It’s my baby,” he said. “I fostered it and watched it grow up. It entertains people and educates people. It’s a blast.”

The 2022 Insect Festival will open Oct. 27. For more information, contact Chad Mills at cmills@uada.edu.

No sunset yet

Steinkraus has been clearing out his office and lab since retiring in June, but he’s not ready to call it quits.

Besides spending time with his wife, Jane, and their family, he has his bees and reams of data from research projects he’s run on the side when he had time. There may yet be research papers to publish.

Steinkraus also plays guitar, including a recently acquired Fender Ultra Telecaster, with two bands. The Velvet Crowns plays original folk-rock written by the band’s lead singer. Git In The Truck plays alternative country.

And that book about teaching insect morphology may still be lingering in the wings.

To learn more about Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website: https://aaes.uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @ArkAgResearch and on Instagram at @ArkAgResearch. To learn more about the Division of Agriculture, visit https://uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @AgInArk.

About the Division of Agriculture

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation’s historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

Pursuant to 7 CFR § 15.3, the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs and services (including employment) without regard to race, color, sex, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, sexual preference, pregnancy or any other legally protected status, and is an equal opportunity institution.

Media Contact: Fred Miller

U of A System Division of Agriculture

Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station

(479) 575-5647

fmiller@uark.edu

Related Links