Cold Comfort

I’ve had a number of calls and emails in the last week about what beekeepers should be doing to help their colonies survive this cold snap. Yankees may shrug it off, but our weather this week in Arkansas - and all across the south - has been unseasonably cold by our standards. Folks say better late than never, but let's be honest... it is the middle of February now. If you haven't done anything to prepare your bee colonies for winter, it really could be too late. You can simply wait and see if that was enough when all this stuff thaws again, or you can bundle up and venture out to check on them.

While northern beekeepers often wrap and insulate hives to prepare for every winter, we don’t usually need to go to extremes here in Arkansas. Our winters are relatively mild, and our bees often have warm “flying days” between brief cold periods. Is this good or bad? And what should we be doing to help our bees make it to spring?

First, it’s good to understand how bees evolved to deal with the cold.

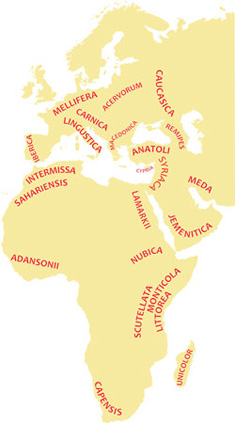

We think our honey bee originated in a warm climate in Africa. The notorious African

honey bees are the same species as our gentle European bees, Apis mellifera. These creatures made their own way through the middle east, around the Mediterranean

Sea and up into Europe. Likely the mid-eastern deserts cut them off from any common

ancestors with the Asian honey bees, of which there are numerous species of Apis. As their populations spread out into all these different environmental niches and

microclimates, they eventually developed into the separate races of honey bees we think of today.

We think our honey bee originated in a warm climate in Africa. The notorious African

honey bees are the same species as our gentle European bees, Apis mellifera. These creatures made their own way through the middle east, around the Mediterranean

Sea and up into Europe. Likely the mid-eastern deserts cut them off from any common

ancestors with the Asian honey bees, of which there are numerous species of Apis. As their populations spread out into all these different environmental niches and

microclimates, they eventually developed into the separate races of honey bees we think of today.

Scientists suspect that honey bees originated in a warm climate because it's terribly inefficient to try to overwinter a large colony, with thousands of nest-mates that require the collection of so much food just to get by. Temperate social bees (like bumble bees) rear new queens each fall, which hibernate alone. The rest of the colony dies out, leaving a handful of mated queens to start new seasonal bumble bee colonies alone. This is why bumble bees don't produce much honey - they only need enough for their day-to-day needs. Pretty much everything our honey bees do in the spring is driven by their need to survive the next winter.

As these African honey bees moved north, they left behind many of their natural enemies, and so they lost some of their ultra-defensive behavior that we associate with African bees and Africanized bees (hybrids of European and African stock that were both imported to the new world). They also began to encounter colder conditions. These winged immigrants to Europe responded to cold weather by clustering together for warmth. They can actively generate heat by vibrating their thoracic wing muscles, similar to the way our muscles shiver when we are cold.

Of course, it takes a lot of energy to produce significant of heat. Luckily for the bees, their favorite food (honey) is high in calories (consider how much energy your children have on the day after Halloween). The reason bees store honey, of course, is to stockpile food for when there are no flowers available. This could be a long dry summer or a long cold winter.

As honey bees adapted to colder climates they also increased the size of their colonies to have a larger winter population cluster, to more efficiently generate sufficient warmth. They also responded by storing up more honey than their tropical counterparts, to fuel these efforts. These are two traits that we enjoy about our western honey bees, and which set them apart from their Africanized cousins. Along with their more docile dispositions, of course.

Honey bees begin to cluster together whenever temperatures get down to 55°F.

Workers will gather together on the brood nest, and around their queen, to keep their vulnerable little larval sisters toasty and warm. This part of the hive actually stays around 92°F any time brood is present. Workers can warm up the brood nest or actively cool it down as needed. Typically in the fall, as flowers become more scarce, the queen slows down her egg production, so there will be little to no brood as winter approaches, and the colony can turn down the heat a little.

Bees naturally store their honey above their brood nest. And now you can see why. Cold conditions cause the cluster to form wherever the queen is. And this is usually in the middle of the brood nest. The cluster will also be near the boundary between brood cells and honey storage, so they have easy access to their food.

The worker bees in the center of the cluster are actively generating heat with their busy wing muscles. Those on the outside of the cluster will rest and form an insulating layer that keeps the warmth trapped inside the cluster. These resting bees can also visit a cell of capped honey and fill their crop. This is like topping off their fuel tank. A bee can hold this honey here in her crop, or release a bit of into their stomach to digest and use it for fuel. They can also expel some honey to share with other bees who need a little snack to keep them going.

The bees in the center of the cluster will eventually need to rest too. They will make their way out to the periphery, and the outside bees eventually move back inward, where they warm up and begin to take another shift as active heaters. All winter long, workers move in and out of the cluster, taking turns.

The cluster itself will slowly move upward as winter proceeds, so that the bees move continuously onto more food as they consume what is in the combs they are on. It helps to visualize the cluster in three dimensions. Our Langstroth hives are stacked rectangular boxes. Think of the cluster as about the size and shape of a football or soccer ball. It’s divided into layers of bees, on different sides of multiple combs. Some bees are actually inside of empty cells, generating heat, which warms the comb, and helps to keep the heat near the clustering bees. Honey bees don’t heat the entire hive, but only keep their cluster warm. We can use special infrared cameras to see exactly where the cluster is in the hive.

In these images above, the brighter yellow shows the warmest spot in the hive – the cluster. The taller hive (on the left) shows the cluster very low, with plenty of room above it. This is an ideal arrangement for the bees in the fall. Assuming that the boxes above are stocked with honey, this colony can last a long time on their canned food, and can survive very cold conditions. The photo on the right shows the location of a cluster that has migrated to the top of the hive. In this situation the colony may be at risk of running out of food, depending on what time of year it is. If spring is still a long ways off, this colony may not survive to see their first dandelion.

The size of the bee cluster changes depending on conditions.

When temperatures drop, the cluster contracts as bees move closer together to conserve that heat. If they become too warm, they will spread apart more loosely, and even open up airways to allow excess heat to chimney up and away, bringing in fresh air from below. When the temperature allows, the cluster can expand and let individual bees reach additional food in different parts of the hive. But when the temperature drops again, they will come back together tightly wherever the mass of bees happens to be at the time.

If the cluster has made it all the way to the top of their hive, and your trusty groundhog has predicted six more weeks, this is not good. Heat rises, and bees move upwards, but will not usually move down. If we happen to have a sudden and prolonged cold snap, such as the one we are currently experiencing in the south, a small colony may cluster tightly in a corner or on one side of the hive. The cluster can move forward or backward, along the orientation of the combs to find more honey. But once that is gone, and if they cannot move upward onto more honey, they could actually die just inches away from a full comb to the side.

In a feral bee hive, a natural tree cavity may be very narrow and very tall. This allows the cluster to potentially span the entire width of the inside of the tree and wrap around all the combs as it travels upwards, with no corners to get stuck in. In larger rectangular hives, with combs in evenly spaced wooden frames, the cluster may not span the entire space in the hive body. Bees can easily move upwards. They can also move forward and backward along the combs if they need to. But moving laterally is more difficult, because the bees must go around the sides of the frames or over the top or underneath. This occasionally causes problems for the bees that may get “cornered” in cold weather. This is one of the disadvantages to modern Langstroth hives, but this fate is usually preventable by making sure the bees are well stocked with food.

A honey bee colony, as a superorganism, can be said to be endothermic – it can generate its own heat like a warm blooded animal.

But on its own, an individual honey bee is exothermic – like a cold blooded animal – and it must rely on heat from its environment to stay alive. When it gets too cold, a single bee will simply slow down and stop moving. If they stay away from their cluster too long, they will slow down, and eventually die.

These photos below show the remains of a weak colony that passed away last year because they had not stored up enough food (and their lousy beekeeper did not notice - yes, I'm guilty). Examining the frames closely reveals that the cluster was quite small, and was all the way over against one side of the hive. The queen (marked with blue) is visible, huddled together with the rest to stay warm. A number of workers have their heads inside of cells, as if they were looking for a last drop of honey.

The only bright side (if one exists) is that this weak colony hosted a lot of small hive beetles. These African beetles survive the winter by hanging out nonchalantly in cells near the bee cluster, hoping they won’t be noticed by the busy bees. When this colony died it took quite a few beetles out with it, since they are not equipped to handle the cold on their own.

"Deadouts" such as this one should be removed from an apiary as soon as they are discovered. Beekeepers are sometimes fooled by bee traffic at the hive entrance on warm days. Robbers from hungry colonies may be removing the honey from dead colonies. But frames with pollen and dead bees may be discovered by scavenging SHB before beekeepers find them later in spring, helping to boost beetle populations in your apiary.

Do bees actually starve to death or do they freeze?

That's a good question. Bees generate heat from the food they consume. They will fill their honey crops, as we discussed, and share that food as needed. Because of this, the entire colony will pass around their last few drops of honey until it’s gone. Individual bees won’t hoard food for themselves. Rather they rely on the group to stay warm, so they feed the rest of the group and rely on the group to keep them fed. It usually works. But when they run out of accessible food, they all die together, rather than one at a time. Or rather, do they run out of energy and grow colder, so they cease to be able to generate heat, and eventually freeze? I’m not sure I can answer that one. It may be interesting to ponder, but it’s just an academic question since they are gone to the great meadow in the sky either way.

But on a practical level, what can we do? Or what should we have done?

What’s the best way to keep our colonies safe and healthy and strong through the winter?

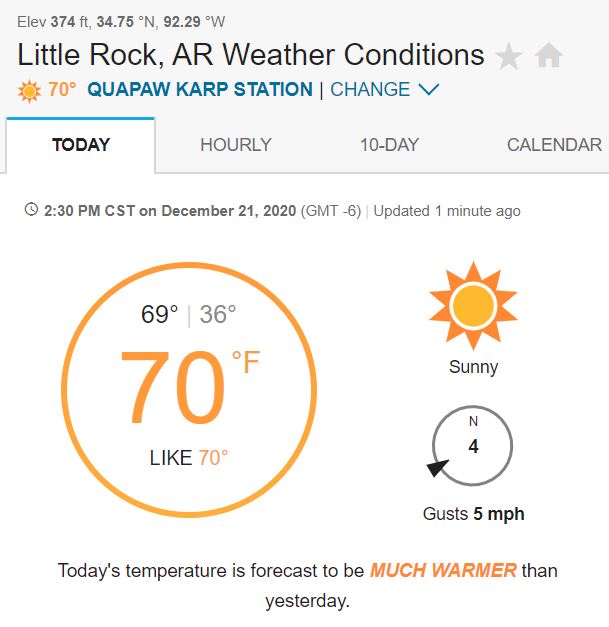

Waiting until February to get your bees ready for the cold doesn’t sound wise. Of

course, we are in Arkansas, where the weather is never a sure thing. After all, it

was 70°F here in Little Rock on the first day of this winter.

Waiting until February to get your bees ready for the cold doesn’t sound wise. Of

course, we are in Arkansas, where the weather is never a sure thing. After all, it

was 70°F here in Little Rock on the first day of this winter.

Our bees have had plenty of sunny flying weather in the last weeks. Many have reported their bees bringing in pollen. And it’s predicted to be up to 58°F again here within a week. Before long the maple trees will pop out, along with willows and ash, and lots of little ground cover too. Surely our little bees can just hold out that long, right?

This period when late winter turns slowly into early spring can be very stressful for our bee colonies. Sporadic warm days (above 55°F) encourage the bees to fly. They take cleansing flights (the polite way to say the bees go out to defecate) and will drag their dead sister out of the hive. They also head out to search for food on warm days. But if they aren’t finding any, they still burn up a lot of calories, which quickly depletes their food stores in the hive. Remaining in their cluster is a very efficient use of their food compared to all this other activity.

This is why a sudden period of extreme cold like this, after so many warm days this winter, can finish off colonies that were getting close to the end of their "canned" food supplies. The only thing that can get them through is access to more food. Honey equals heat for wintering bees. If they still have honey in the hive, they should be fine. If they don’t, then beekeepers need to intervene.

Overwintering your bees successfully actually started late last summer.

When did you harvest your honey? After you took your share of the gold, you should have begun assessing your bee colonies’ health. Varroa mites remain the #1 enemy of the honey bee. The viruses that these mites vector are also bad. Together the mite-virus complex is worse than the sum of its parts. Varroa mites physically wound the honey bees and impair their immune system, while at the same time infecting them with potentially multiple viruses. There are around 30 honey bee viruses that we know about. Only a few, such as Deformed Wing Virus or Sacbrood Virus, produce obvious symptoms that we can identify. Most viruses are invisible, and simply make the bees weaker, shorten their lives, and generally make a colony less efficient at pollinating, producing honey, rearing brood, and generating that important winter warmth.

There are no silver bullets for varroa mites. Most of the products and medications we have cannot be used when honey is on the hive. Some are very sensitive to temperature. Others are only effective when there is no brood in the hive. Some leave chemical residues in the wax, and can affect bee health if not used properly. Some products fall into several, or all, of these categories at once.

What’s a beekeeper to do about varroa mites?

Do your best! Do your homework! Do something! Monitor your colonies and try to keep your mite levels below 3% infestation. If you don't like chemical approaches, there are organic methods of mite control. These usually involve more labor per hive for the beekeeper. The methods that are less laborious for beekeepers tend be medications that can also have some side effects on bees. You’ll have to decide where your beekeeping operations falls within this spectrum. But be aware of mites, and know that they have a big effect on overwintering success.

In order to survive the winter and thrive in spring, a bee colony needs to be healthy and well fed, not just with honey, but with protein too.

Bees need pollen, which is full of proteins, amino acids, and other nutrients. They store up proteins in an organ which entomologists call the fat body. They use these stored proteins to metabolize the rich royal jelly which they feed to their queen bee and to all the new larvae. During the spring and summer, when flowers are abundant, so is royal jelly, and the population increases. In the winter, bees rely on this stored protein to rear a small patch of brood even into November or beyond in the south. They will often begin brood rearing again by late January or early February here. Bees must rely on these stored proteins until the first spring flowers begin to bloom, and they can collect fresh food again form the outside.

A heavy varroa mite infestation removes proteins from developing bees and can affect numerous metabolic processes later in their adult life phase. They will be less efficient at brood rearing, so the brood they produce is also less healthy. Even if you successfully treat a colony and rid it of every varroa mite, the bees in it can still be in poor health. They must rear the next generation of workers, which may not be infested with mites or infected with viruses, but were fed by a generation of weak bees, and may have less than optimal health. These bees, in turn can raise a new generation of stronger bees, and so on. It can take three or more brood cycles for a colony to fully recover from a heavy varroa infestation.

This is why overwintering success starts in the late summer, after harvesting honey, to put our bees on the right track. These summer bees might be weak, but will produce the fall bees, which are stronger, and ultimately the cohort of overwintering bees that should be well fed on protein, have low virus levels, and will be ready to go the distance.

Good bee health is part of the picture. The other is plenty of food.

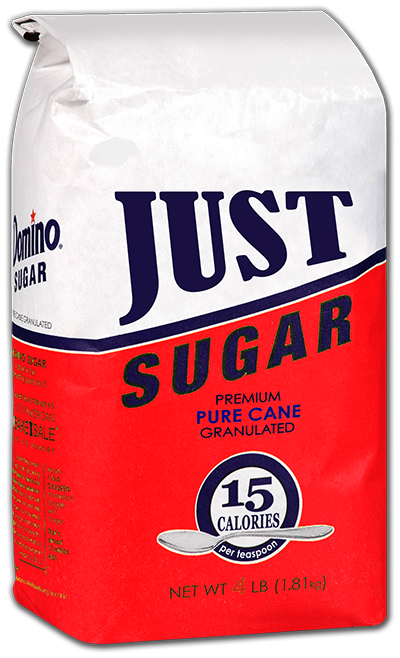

Honey is the best food for bees, because it contains tiny bits of pollen and other enzymes. If you have taken too much honey, or the bees did not store up enough, then you will have to supplement with a sugar syrup to get them through the winter. Honey is best, of course, but syrup will usually get them through.

Feed honey bees pure white refined sugar – sucrose.

Feed honey bees pure white refined sugar – sucrose.

Don’t feed them brown sugar or molasses. Don't try to treat them to organic raw cane sugar. These sugars are darker because they contain things the bees can’t digest, which can cause other issues in the hive if they can’t get out to relieve themselves. Pure sucrose is close to what flower nectar contains. Read a previous post on sugar compositions if you are curious about more details.

When you feed bees in the winter, remember to put the syrup as close to them as possible. Don’t use an entrance feeder in cold weather. With the cluster at top of the hive, a single worker bee can’t make her way from the hungry cluster at the top of the hive, down to the feeder, and then back up without getting too cold to return. You will end up with a layer of dead bees in the bottom of the hive who tried, but failed, and a small cluster of dead ones at the top who were waiting for their sisters to return with lunch.

An internal feeder, such as a division board feeder, placed on the edge of the hive can work. You will only have to move the lid slightly over to refill it, and the bee cluster will likely migrate right over next to it (if they can) so that a steady stream of bees can move down in and back out with food. Be careful when you refill, to avoid drowning the bees inside.

Another good option is a jar or bucket feeder (or similar style) placed right above the hole in the inner cover. You’ll need an empty super to go over it, of course. But these are easy to refill or swap out when empty. And you will find that the cluster of bees will gather just below it. There are many other methods of feeding bees, but you should consider how close you can get the food to the ones who need it most.

Another great way to insure bees stay fed are candy boards. As the name implies, these are big blocks of sugar candy (either solid rock candy or softer fondant) placed on top of the hive, often inside of wooden frames. With one of these on the hive, wherever the cluster happens to be when they reach the top and run out of honey, the ceiling above them is made of food! Humidity in the hive will soften the outermost surface of this candy enough for the bees to eat it. You can buy these already prepared or make your own. There are many recipes online, and most are pretty simple. Some variations include mixing in protein powders or essential oils that stimulate consumption. Some beekeepers even bury a protein patty under a layer of candy, so that when the bees have begun eating the candy, they will get to the protein just as they are beginning to rear brood in the early spring.

Candy boards are good insurance. A big block of sugar won’t spoil. So if your bees didn’t eat it after all, wrap it up and store it in the freezer for next winter. If they did eat it, then it means you made the right choice to have it available. Good job!

What about wrapping hives?

Many northern beekeepers will wrap their hives with tar paper and layers of insulation. We don’t do this in the south. You could, but we just don’t have the same conditions for any extended period (although this week it seems like another ice age may be upon us). Do slide in the boards that close off your screen bottoms (if you have them). Bees don’t lose much heat out of the bottom of the hive, but cold drafts on windy days can chill small brood nests and make it harder for the bees to regulate the temperature.

An average size bee colony needs 45-50 pounds of honey for a “normal” winter in Arkansas (whatever that is anymore). For reference, this is a little more than a medium super can hold, but a little less than a full deep box. Just remember that too many warm days means bees consume food faster than if stays below 55°F all winter long. Adjust your strategy accordingly.

How do you know if your bees have enough to eat?

You can check on them by peeking under the lid, even in very cold conditions. Just don’t leave the hive open for long, and don’t pull out frames that break up the cluster. Be mindful that honey bees don’t like to be surprised, and opening their warm dark hive without warning on a bright, freezing day is going to be a shock to them. Some might seem to launch themselves at you stinger first! This is their way of asking you politely to close the door, it's cold outside. Dress appropriately with veil and gloves. You may not need them, but if your bees don’t make you feel welcome, you’ll be glad you did!

The easiest way to check your hives is to simply lift off the lid.

Do you see bees just under the hole in the inner cover? That’s all you need to know. Your colony is at the top of the hive. You could place a jar feeder or block of candy right above them, and check in a week to see if they need more. Be careful that your syrup jar is not dripping and draining out, which will get them wet and can chill them. The syrup should form a light vacuum seal when inverted, so they have to touch it with their tongues to get a drink.

If you open the lid and don’t see bees, gently remove the inner cover. Do you seem them now? Are they at the top? If so, then they may need help. Can you hear them buzzing below, but can’t see them? If that’s the case, they probably still have sufficient food stored above them that they have not moved onto yet. Close up the hive and check again later, or supplement what they have, just to be on the safe side. You will have to make a judgment call based on the size of the cluster, where the it is located and your best guess about how much longer until spring.

Are you still not sure your bees have enough food? Err on the side of caution. You can get four pounds of sugar for less than $3.00. That's cheap insurance for a colony that will cast you well over $100 to replace.

As an emergency measure, because you just found a colony that is on the brink of starvation and you have no prepared any syrup or candy, you could just dump a bunch of granulated sugar in there and hope for the best (some call this the mountain camp method). Simply place a sheet of paper across the tops of the frames just above the bees, but a little to the side, so they can come up around the edge. Pour a cup or two of dry sugar onto the paper, which is there to keep the sugar from falling through the frames. Spritz the sugar very lightly with a mist of water to help the bees begin to feed it. Don’t make it too wet, or you will create a big mess. If the bees are just under the inner cover, you could simply pour sugar on top of it, again with a light spray of water. Push some softened sugar right to the edge, so your bees can find it, and encourage them to climb up and get more.

It’s always better to plan ahead, and go into winter with colonies you are confident are healthy and well-fed, with ample stored food. But if this weather has prompted you to wonder about your hives, using any method you can devise to deliver food directly to a hungry cluster of bees is going to be better than nothing.