COVID-19 Vaccines - Facts and Information

Updated Booster Doses Now Available

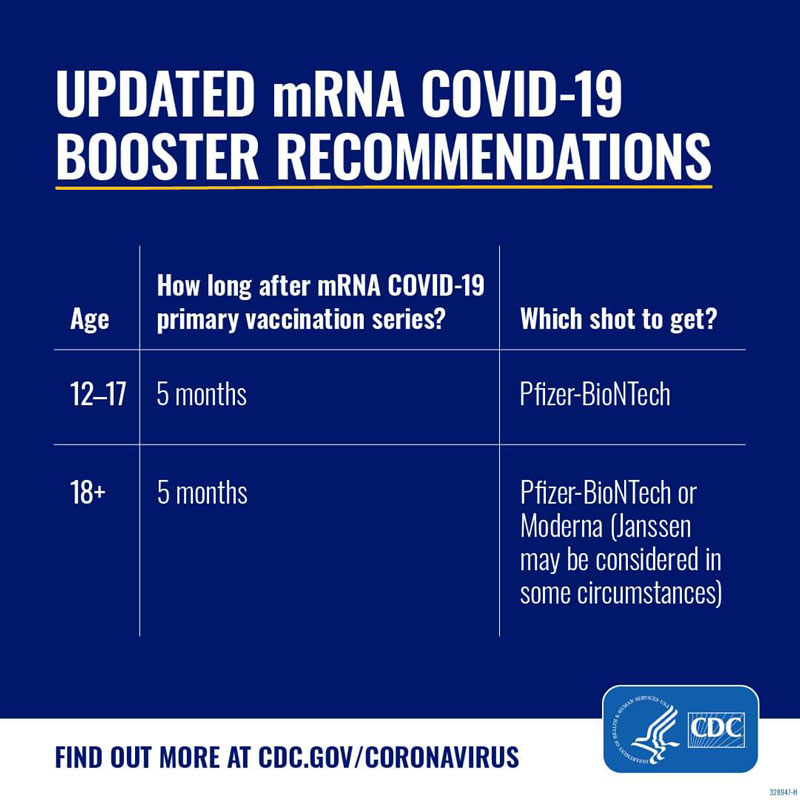

On September 1, 2022, the CDC issued new recommendations for COVID-19 boosters, after the FDA authorized updated booster formulas from both Pfizer and Moderna. The CDC recommends that everyone who is eligible stay up-to-date on vaccinations by getting an updated booster dose at least 2 months after their last COVID-19 shot—either since their last booster dose, or since completing their primary series. Pfizer’s updated booster shot is recommended for individuals 12 and older, and Moderna’s updated booster shot is recommended for adults 18 and older.

These new boosters contain an updated bivalent formula that both boosts immunity against the original coronavirus strain and also protects against the newer Omicron variants that account for most of the current cases. Updated boosters are intended to provide optimal protection against the virus and address waning vaccine effectiveness over time.

Eligible individuals can get either the Pfizer or Moderna updated booster, regardless of whether their primary series or most recent dose was with Pfizer, Moderna, Novavax, or the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

As per the CDC’s recommendations, the new bivalent booster replaces the existing monovalent vaccine booster, therefore that vaccine will no longer be authorized for use as booster doses in people age 12 and up.

Yes, the CDC recommends that everyone age 12 and up should get an updated COVID-19 booster this fall to stay up-to-date on vaccinations. The same is true for people who completed their primary series or received one or two boosters: they should get an updated booster dose at least two months after their last shot.

For maximum effectiveness of the updated booster dose, individuals who recently had COVID-19 may consider delaying any COVID-19 vaccination, including the updated booster dose, by 3 months from the start of their symptoms or positive test.

No. The updated bivalent formula is in use only for COVID-19 booster doses, and not for initial vaccination. The best way to protect yourself from getting severely ill from COVID-19 is to get vaccinated. The CDC recommends that currently unvaccinated people get their primary series (the initial two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna, or one dose of the Novavax vaccine), and then wait at least two months to get the updated Pfizer or Moderna booster dose.

Booster doses are common for many vaccines, and over time, booster doses may need to be updated to provide optimal protection against new variants of the virus. The scientists and medical experts who developed the COVID-19 vaccines continue to watch for waning immunity, how well the vaccines protect against new mutations of the virus, and how that data differ across age groups and risk factors.

To date, booster doses have worked well in extending the protection of the vaccine against serious illness, but have been somewhat less effective in boosting immunity against new variants of COVID-19 compared to the original strain. The updated booster dose formula is designed to protect against original strains of the virus, as well as Omicron variants that account for the majority of current new infections.

The latest CDC recommendations on booster doses help to ensure more people across the U.S. are better protected against COVID-19. The best way to protect yourself from COVID-19 is to get vaccinated and boosted if eligible. Vaccination and boosting is particularly important for individuals more at risk for severe COVID-19, such as older people and those with underlying medical conditions.

Yes. Eligible individuals can get either the Pfizer or Moderna updated booster, regardless of whether their primary series or most recent dose was with Pfizer, Moderna, Novavax, or the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Yes. The CDC recommends that everyone 6 months and older get a flu vaccine every season, which occurs in the U.S. in the fall and winter. The best time to get your flu shot is in September or October before the flu is spreading in your community.

Based on CDC guidance, the COVID-19 vaccines can be given the same day as other vaccines, including the flu vaccine. Some people choose to get each shot in a different limb to minimize possible discomfort. Ask your health provider if you have any questions about getting either or both vaccines.

COVID-19 Booster Eligibility:

Everyone age 12 and older is eligible to get a COVID-19 booster dose.

The CDC recommends that people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine get a Pfizer or Moderna booster. The CDC advises people who got a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine to get the same booster as their initial vaccine, but allows them to mix and match (i.e., get a different COVID-19 booster than their initial vaccine) depending on preference or availability—with the exception of adolescents age 12-17 who are only eligible to receive the Pfizer vaccine If you have questions about your eligibility for booster doses or which booster you should get, speak to your health care provider.

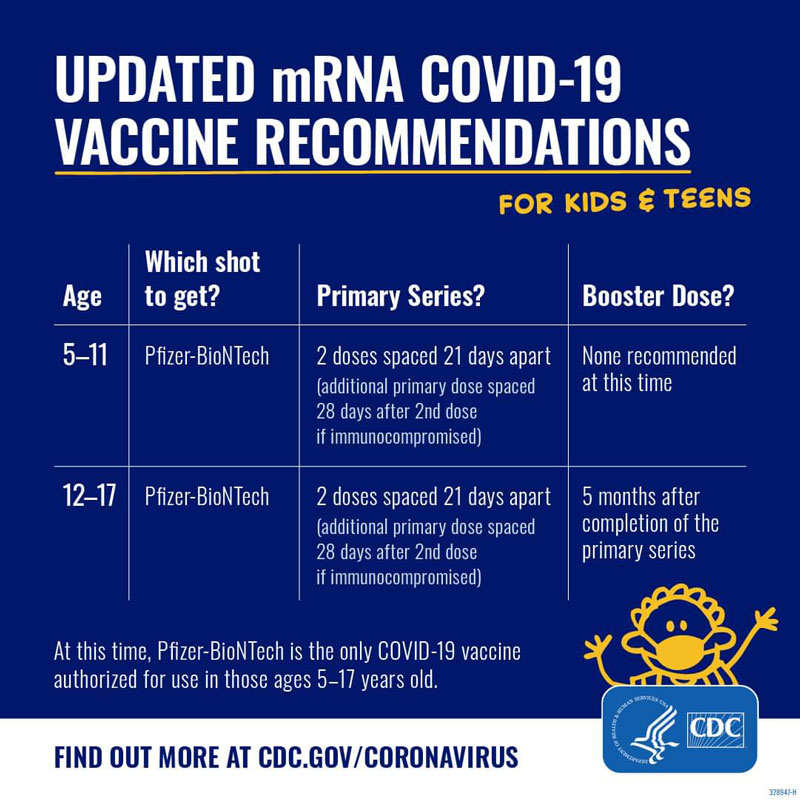

Children and Vaccinations

The CDC recommends that children and adolescents age 5 and older get a COVID-19 vaccine. The Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine is authorized for children and adolescents age 5 and up, as a 2-dose series taken 3 weeks apart. The dose for children age 5-11 is one-third of the dosage of the vaccine for older adolescents and adults. Vaccination is the best way to protect children age 5 and older from COVID-19. COVID-19 has become one of the top 10 causes of pediatric death, and tens of thousands of children and teens have been hospitalized with COVID-19. While children and adolescents are typically at lower risk than adults of becoming severely ill or hospitalized from COVID-19, it is still possible. The vaccine is safe and effective. Before being authorized for children, scientists and medical experts completed their review of safety and effectiveness data from clinical trials of thousands of children. The Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine was rigorously tested and reviewed, and more than 11 million adolescents ages 12-17 have already safely received the COVID-19 vaccine. |

Omicron Variant Information

What is the Omicron variant?

Omicron is a new variant of the virus that causes COVID-19. The Omicron variant has been detected in a growing number of countries, including the U.S.

Is Omicron as serious a health risk as other variant? Is it more or less contagious?

While health officials are still collecting data to answer these questions fully, we know that Omicron can be serious, especially for those who are not vaccinated. Omicron spreads more quickly and more easily than the Delta variant and may evade our immune system’s defenses. Even those who are vaccinated can spread Omicron to others. However, the best way to protect yourself from serious illness and hospitalization due to the Omicron variant is to get vaccinated, and if you are vaccinated, to get a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

Are the vaccines effective against this variant?

Current vaccines are expected to protect against severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths due to infection with the Omicron variant. However, breakthrough infections in people who are fully vaccinated are likely to occur. With other variants, like Delta, vaccines have remained effective at preventing severe illness, hospitalizations, and death. The recent emergence of Omicron further emphasizes the importance of vaccination and boosters.

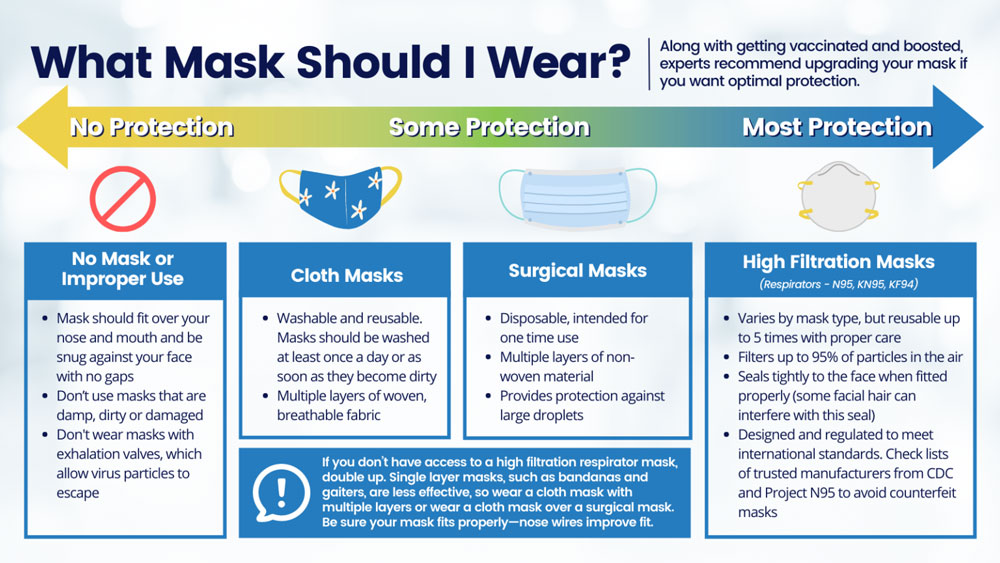

Should I upgrade my mask? How do I know which masks will protect me?

Along with getting vaccinated and boosted, wearing a well-fitting mask over your mouth and nose in indoor public settings or crowds (whether indoors or outside) is crucial to preventing the spread of COVID-19. With the rapid spread of the Omicron variant, experts are recommending that consumers upgrade their mask to a high filtration respirator if they want optimal protection.

Delta Variant Information

Yes. Vaccination is the best protection against Delta.

The most important thing you can do to protect yourself from Delta is to get fully

vaccinated, the doctors say. That means if you get a two-dose vaccine like Pfizer

or Moderna, for example, you must get both shots and then wait the recommended two-week

period for those shots to take full effect.

Whether or not you are vaccinated, it’s also important to follow CDC prevention guidelines that are available for vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

Unvaccinated people are at risk.

People who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19 are most at risk. In the U.S., there is a disproportionate number of unvaccinated

people in Southern and Appalachian states including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi,

Missouri, and West Virginia, where vaccination rates are low (in some of these states,

the number of cases is on the rise even as some other states are lifting restrictions

because their cases are going down).

Kids and young people are a concern as well. “A recent study from the United Kingdom

showed that children and adults under 50 were 2.5 times more likely to become infected

with Delta,” says Dr. Yildirim.

And so far, no vaccine has been approved for children 5 to 12 in the U.S., although

the U.S. and a number of other countries have either authorized vaccines for adolescents

and young children or are considering them.

“As older age groups get vaccinated, those who are younger and unvaccinated will be

at higher risk of getting COVID-19 with any variant,” says Dr. Yildirim. “But Delta seems to be impacting younger age groups more than

previous variants.”

Yes. Delta is the name for the B.1.617.2. variant, a SARS-CoV-2 mutation that originally surfaced in India. The first Delta case was identified in December 2020, and the strain spread rapidly, soon becoming the dominant strain of the virus in both India and then Great Britain. Toward the end of June, Delta had already made up more than 20% of cases in the U.S., according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates. That number is rising swiftly, prompting predictions that the strain will soon become the dominant variant here.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called this version of the virus “the fastest

and fittest.” In mid-June, the CDC labeled Delta as “a variant of concern,” using

a designation also given to the Alpha strain that first appeared in Great Britain,

the Beta strain that first surfaced in South Africa, the two Epsilon variants first

diagnosed in the U.S., and the Gamma strain identified in Brazil. (The new naming

conventions for the variants were established by the WHO at the beginning of June

as an alternative to numerical names.)

“It’s actually quite dramatic how the growth rate will change,” says Dr. Wilson. Delta

is spreading 50% faster than Alpha, which was 50% more contagious than the original

strain of SARS-CoV-2—making the new variant 75% more contagious than the original,

he says. “In a completely unmitigated environment—where no one is vaccinated or wearing

masks—it’s estimated that the average person infected with the original coronavirus

strain will infect 2.5 other people,” Dr. Wilson says. “In the same environment, Delta

would spread from one person to maybe 3.5 or 4 other people.”

“Because of the math, it grows exponentially and more quickly,” he says. “So, what seems like a fairly modest rate of infectivity can cause a virus to dominate very quickly—like we’re seeing now. Delta is outcompeting everything else and becoming the dominant strain.”

Single-dose vaccine joins battle against COVID-19

Download this PDF that compares the new single-dose vaccine to the existing two-dose vaccines.

En Espanol

La vacuna de una dosis se une a la lÌnea de vacunas de dos dosis, en la batalla contra COVID-19

A Primer on COVID-19 Vaccines

Download this primer as a PDF.

COVID-19 has followed us into 2021. The news of multiple successful vaccines has renewed hope and allowed us to look ahead and imagine of some semblance of a new normal in 2021 and beyond. As of this writing, the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use authorization (EUA) to begin Phase 1 of inoculating our population against SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes COVID-19 disease.

As updates are available, and as new vaccines come online and also seek approval for emergency use authorization by the FDA, updates will be made to this document. Specifically, with regard to the process for everyone in Phases 2 and beyond to receive the vaccine, clearer recommendations will be made and this document will be updated to reflect those changes.

What does our immune system have to do with vaccines?

To better understand how the new COVID-19 vaccines work, we first need to talk about our immune system. When the virus that causes COVID-19 gets into our bodies, usually by breathing in aerosol droplets created when someone else talks, coughs, blows their nose, or breathes, those virus particles attack our bodies and begin to multiply. Once enough virus particles have been created inside your body you may become sick and you can then easily spread the virus on to other people that you come into contact with on a daily basis.

The immune system—our body’s defense system against infections—goes to work quickly against foreign germs like the virus that causes COVID-19 disease. When we are infected with a new virus that our body has not encountered before, our immune system can take awhile to “catch up” to the virus and create enough virus-killing cells to combat COVID-19. Once the body creates enough virus-killing cells, your immune system puts them to work against the virus, eventually making you feel better.

One of the key types of cells doing the heavy lifting of fighting off the virus are T-lymphocytes—you may know them as T-cells. Remarkably, these T-cells can remember how it fought off a particular infection. In the case of COVID-19 disease, if someone who had COVID-19 encounters the virus again, those T-cells remember the virus and send viral antibodies to attack the virus much more quickly than the first time, providing partial immunity. Researchers are still discovering how long this natural immunity may last.

How do COVID-19 vaccines work?

Vaccines are one tool in our collective toolbox to fight off COVID-19. Preventing exposure by wearing a mask, washing your hands, and social distancing helps to reduce your chances of getting COVID-19.

While different vaccines work in different ways (more on that later), all of the COVID-19 vaccines give the body a supply of those T-cells, like the ones mentioned above, that remember how to fight the virus in the future. The vaccines help your body build up a huge number of these T-cells, as well as another type of cell called B-lymphocytes, whose job it is to finish off any virus molecules not killed off by T-cells and other early responders. This process of building up defensive cells usually takes a few weeks, so it is important to continue practicing the wearing of a mask, the washing of your hands, and the social distancing from others, even after you are vaccinated.

The Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines

Yes. The CDC recommends everyone 12 years and older should get a COVID-19 vaccination to help protect against COVID-19. Widespread vaccination is a critical tool to help stop the pandemic. People who are fully vaccinated can resume activities that they did prior to the pandemic. Learn more about what you and your child or teen can do when you have been fully vaccinated. Children 12 years and older are able to get the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine.

Getting a COVID-19 vaccination can help protect your child from getting COVID-19. Early information shows that the vaccines may help keep people from spreading COVID-19 to others. They can also help keep your child from getting seriously sick even if they do get COVID-19. Help protect your whole family by getting yourself and your children 12 years and older vaccinated against COVID-19.

All COVID-19 vaccines were tested in clinical trials involving tens of thousands of people to make sure they meet safety standards and protect adults of different ages, races, and ethnicities. There were no serious safety concerns. CDC and the FDA will continue to monitor the vaccines to look for safety issues after they are authorized and in use.

No. None of the COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized for use, or in development, in the United States use the live virus that causes COVID-19. However, it typically takes two weeks for the body to build stronger immunity after the second dose of an mRNA vaccine or after the single–dose Janssen vaccine. Therefore, it is particularly important to continue to follow all public health guidance, such as wearing a mask, watching your distance, and washing your hands, especially before protection from the vaccine has been built (when you are still fully susceptible to become infected and get sick from COVID-19.)

According to NIH’s Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett: “There are no tracking devices whatsoever in the vaccine. I was the scientific lead [at NIH], and in the last six years we gathered fundamental understanding of how to make vaccines for coronaviruses. They caused MERS in 2014, and SARS before that. We have fundamental knowledge around coronaviruses. We have looked at the protein at atomic detail, we understand every nook and cranny and antibody response. What you see in front of you appears like 10-11 months of vaccine development, but the preclinical science extends beyond my tenure at NIH, 10-15 years starting with SARS, so there’s a large amount of research backing it.”

No. The mRNA from COVID-19 vaccines can most easily be described as a set of instructions for your body for how to make a harmless piece of “spike protein” to allow our immune systems to recognize that this protein doesn’t belong there and begin building an immune response and making antibodies. Essentially, COVID-19 vaccines that use mRNA work with the body’s natural defenses to safely develop immunity to the virus, giving your cells a blueprint of how to make antibodies.

No. Time after time, studies conducted across the globe continue to show that there is no connection between autism and vaccines.

COVID-19 vaccination will help protect you from getting COVID-19 by stimulating your immune system so your body is ready to respond if you come in contact with the virus. You may expect to have some side effects, which are normal signs that your body is building protection. These side effects may affect your daily life, but they should go away in a few days. Common side effects are pain and swelling in the arm where you received the shot, fever, chills, tiredness, and headache. Some of these may be more severe if you have been previously infected with COVID-19 and, in the case of mRNA vaccines, after the second dose.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is globally respected for its scientific standards of vaccine safety, efficacy, and quality. In an emergency, like a pandemic, the FDA can make a judgement that it is worth releasing a vaccine, drug, device and/or test for use even without all the evidence that would go into the normal approval process. That judgement, in this case that the known and potential benefits of a COVID-19 vaccine must outweigh the known and potential risks of the vaccine, is called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). Under both EUA and normal approval, the FDA provides scientific and regulatory requirements to vaccine developers and undertakes a rigorous evaluation of the scientific information through all phases of clinical trials, which continues after authorization or approval. Clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines must first show they are safe and effective before any vaccine can be issued an EUA.

Yes. COVID-19 vaccination is especially important for people with underlying health problems like heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, and obesity. People with these conditions are more likely to get very sick from COVID-19.

CDC recommends that people with a history of severe allergic reactions that are not related to vaccines or injectable medications—such as food, pet, venom, environmental, or latex allergies—get vaccinated. People with a history of allergies to oral medications or a family history of severe allergic reactions may also get vaccinated.

Tell the provider about your allergy when you get the vaccine. They are prepared to

administer the vaccine safely and provide treatment in the rare case of allergic reactions.

As a precaution, the CDC guidelines recommend that those with allergies be observed

at the site for 30 minutes instead of 15 minutes. But it is not something to prevent

you from getting vaccine.

Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccines

Based on the current research, the Janssen (J&J) vaccine (one dose) and the Pfizer/BioNTech and the Moderna vaccines (both two-dose regimens) are incredibly good at preventing people from getting sick with COVID-19. (Janssen with 72% vaccine efficacy [83.5% against severe disease], Pfizer/BioNTech with 95% efficacy and Moderna with 94.1% efficacy).

The Janssen, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are all proven to be safe and effective in preventing COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths. Getting vaccinated with any of these vaccines will greatly reduce your risk of serious illness due to the virus, and it is recommended that you take the first vaccine available to you.

The single-dose Janssen vaccine has been shown to be 85% effective in preventing severe

illness from COVID-19 and 100% effective against COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths.

In trials, the vaccine also lowered the risk of moderate-to-severe COVID-19 illness

by 72% among people who were vaccinated compared to people who received the placebo.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine showed efficacy of 95% at preventing symptomatic COVID-19

infection after two doses, and the Moderna vaccine was 94.1% effective at preventing

symptomatic COVID-19 infection after the second dose.

After you are vaccinated, it takes some time for your body to build an immune response to the vaccine. CDC advises that the vaccines offer strong protection starting two weeks after completing the vaccination series (one dose for Janssen, two doses for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines).

Once you get vaccinated, you will have a lower risk of getting sick from COVID-19. However, no vaccine provides 100% immunity and many people around you are likely to be unvaccinated.

To protect others, it is crucial to continue practicing the 3 W’s:

- Wear a mask

- Wash your hands

- Watch your distance until enough people are vaccinated to stop the spread of the virus.

Yes. Fully vaccinated individuals should continue to practice the 3 W’s—wear a mask, wash your hands, and watch your distance. There is some evidence that vaccinated people can carry and transmit COVID-19 and its variants, like the Delta variant.

According to CDC as of August 18, 2021, to maximize protection from the Delta variant and prevent possibly spreading it to others, wear a mask indoors in public if you are in an area of substantial or high transmission.

To protect yourself and others, follow these recommendations in public:

- Wear a mask over your nose and mouth

- Stay at least 6 feet away from others

- Avoid crowds

- Avoid poorly ventilated spaces

- Wash your hands often

See the CDC’s guidelines for fully vaccinated individuals

UPDATE: There is emerging evidence (1, 2, 3) that mixing COVID-19 vaccines may produce a strong immune response, however the current CDC recommendations still suggest that you should not mix vaccine doses at this time, due to the lack of sufficient evidence. As more is learned about the mixing of doses, updates will be made.

Not usually. The COVID-19 vaccines are not interchangeable, and the safety and efficacy of a mixed-product series have not been evaluated. However, if two doses of different mRNA COVID-19 vaccine products are inadvertently administered, no additional doses of either product are recommended at this time.

In exceptional situations in which the first dose of an mRNA vaccine product cannot be determined or is no longer available, any available mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be administered at a minimum interval of 28 days between doses to complete the mRNA COVID-19 vaccination series. Only one dose of J&J vaccine is needed and recommended at this time.

Recommendations may be updated as further information becomes available or other vaccine types (e.g., viral vector, protein subunit vaccines) are authorized

The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine includes two shots, 21 days apart while the Moderna vaccine includes two shots, 28 days apart. Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine efficacy after a single dose was 52.4% in trials; Moderna’s was 80.2%.

However, both doses are currently recommended to get the maximum protection, since

there have been no clinical trials assessing these mRNA vaccines as single dose regimes.

Until more is learned about the duration and kind of protection you get from the vaccine,

you should take the same precautions you did before vaccination. Moreover, until the

population is broadly vaccinated, and the outbreak is under control, which will take

many months, everyone — vaccinated or not— needs to continue to wear masks and practice

distancing to protect themselves and others.

Yes. CDC recommends that you get vaccinated even if you have already had COVID-19. While you may have some short-term antibody protection after recovering from COVID-19, we don’t know how long this protection will last, and it is possible to catch it more than once.

Vaccination of a person with known current SARS-CoV-2 infection should be deferred until they have recovered from the acute illness (if they had symptoms) and they have met criteria to discontinue isolation. This recommendation applies to people who become infected before receiving any vaccine dose and those who become infected after the first dose of an mRNA vaccine but before receipt of the second dose.

While there is no recommended minimum interval between infection and vaccination, current evidence suggests that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection is low in the months after initial infection but may increase with time due to waning immunity. Thus, while vaccine supply remains limited, people with recent documented acute SARS-CoV-2 infection may choose to temporarily delay vaccination, if desired, recognizing that the risk of reinfection and, therefore, the need for vaccination, might increase with time following initial infection.

The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine includes two shots, 21 days apart while the Moderna vaccine includes two shots, 28 days apart.

Persons should not be scheduled to receive the second dose earlier than recommended

(e.g., 3 weeks [Pfizer-BioNTech] or 1 month [Moderna]). However, second doses administered

within a grace period of 4 days earlier than the recommended date for the second dose

are still considered valid. Doses inadvertently administered earlier than the grace

period should not be repeated.

If it is not feasible to adhere to the recommended interval, the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech

and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines may be scheduled for administration up to 6 weeks (42

days) after the first dose. There are currently limited data on efficacy of mRNA COVID-19

vaccines administered beyond this window. If the second dose is administered beyond

these intervals, there is no need to restart the series.

Experts do not know exactly what percentage of people would need to get vaccinated to achieve herd immunity to COVID-19. The current estimation is between 70-85%. Herd immunity is a term used to describe when enough people in a community have protection—either from previous infection or vaccination—that it is unlikely a virus or bacteria can spread and cause disease. As a result, everyone within the community is protected, even if some people do not have any protection themselves. The percentage of people who need to have protection in order to achieve herd immunity varies by disease.

Clinical trials are studies to assess the safety and efficacy of vaccines. They are typically conducted in three phases, each with increasingly larger numbers of volunteers.

- Phase 1 clinical trials assess the safety and dosage of a vaccine in a small number of people, typically a dozen to several dozen healthy volunteers.

- Vaccine safety is also assessed in Phase 2 studies, in which adverse events not detected in phase 1 trials may be identified because a larger and more diverse group of people receive the vaccine.

- Only in much larger Phase 3 clinical trials can it be demonstrated whether a vaccine is actually protective against disease. Safety is also more fully assessed. Phase 3 clinical trials often include thousands of volunteers, and for Covid-19 vaccines will involve tens of thousands (30,000 to 45,000 people in some of the ongoing phase 3 trials).

All three phases of clinical trials were completed for all currently available COVID-19 vaccines.

Natural immunity refers to the process of building an immune response to a disease after being infected by it. After getting COVID-19, most people will build an immune response that will last at least a few months and help fight the disease if they are exposed to it again, so they do not become sick.

After completing a COVID-19 vaccination, people are expected to build a vaccinated-immune

response that will last months and help their immune system fight COVID-19 if they

are exposed to it, so they do not become sick.

Experts are still studying how long natural and vaccine-induced immunity will last

for COVID-19. There may also be differences in the level of immune response from natural

immunity versus vaccine-induced immunity and scientists are continuing to study this

area.

Both of these processes are types of active immunity, where the body responds to something

from the outside world to build the immune response. Active immunity is different

from passive immunity, where someone is given antibodies rather than their body producing

antibodies through active immunity.

Three things to know about the Delta variant of COVID-19:

- Delta is more contagious than the other viral strains.

Delta is the name for the B.1.617.2. variant, a SARS-CoV-2 mutation that originally surfaced in India. The first Delta case was identified in December 2020, and the strain spread rapidly, soon becoming the dominant strain of the virus in both India and then Great Britain. Toward the end of June, Delta had already made up more than 20% of cases in the U.S., according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates. That number is rising swiftly, prompting predictions that the strain will soon become the dominant variant here.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called this version of the virus “the fastest and fittest.” In mid-June, the CDC labeled Delta as “a variant of concern,” using a designation also given to the Alpha strain that first appeared in Great Britain, the Beta strain that first surfaced in South Africa, the two Epsilon variants first diagnosed in the U.S., and the Gamma strain identified in Brazil. (The new naming conventions for the variants were established by the WHO at the beginning of June as an alternative to numerical names.)

“It’s actually quite dramatic how the growth rate will change,” says Dr. Wilson. Delta is spreading 50% faster than Alpha, which was 50% more contagious than the original strain of SARS-CoV-2—making the new variant 75% more contagious than the original, he says. “In a completely unmitigated environment—where no one is vaccinated or wearing masks—it’s estimated that the average person infected with the original coronavirus strain will infect 2.5 other people,” Dr. Wilson says. “In the same environment, Delta would spread from one person to maybe 3.5 or 4 other people.”“Because of the math, it grows exponentially and more quickly,” he says. “So, what seems like a fairly modest rate of infectivity can cause a virus to dominate very quickly—like we’re seeing now. Delta is outcompeting everything else and becoming the dominant strain.”

- Unvaccinated people are at risk.

People who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19 are most at risk. In the U.S., there is a disproportionate number of unvaccinated people in Southern and Appalachian states including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, and West Virginia, where vaccination rates are low (in some of these states, the number of cases is on the rise even as some other states are lifting restrictions because their cases are going down).

Kids and young people are a concern as well. “A recent study from the United Kingdom showed that children and adults under 50 were 2.5 times more likely to become infected with Delta,” says Dr. Yildirim. And so far, no vaccine has been approved for children 5 to 12 in the U.S., although the U.S. and a number of other countries have either authorized vaccines for adolescents and young children or are considering them.

“As older age groups get vaccinated, those who are younger and unvaccinated will be at higher risk of getting COVID-19 with any variant,” says Dr. Yildirim. “But Delta seems to be impacting younger age groups more than previous variants.” - Vaccination is the best protection against Delta.

The most important thing you can do to protect yourself from Delta is to get fully vaccinated, the doctors say. That means if you get a two-dose vaccine like Pfizer or Moderna, for example, you must get both shots and then wait the recommended two-week period for those shots to take full effect.Whether or not you are vaccinated, it’s also important to follow CDC prevention guidelines that are available for vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

Viruses frequently change through mutation, and new variants of a virus are expected to occur over time. Multiple variants of the virus that causes COVID-19 have been documented in the U.S. and globally during this pandemic. This includes the B 1.351, B.1.1.7 and P.1 variants first detected in South Africa, the United Kingdom, and Brazil, respectively. Data suggest that these variants spread more easily and quickly than other variants.

As a result, it is very important for everyone to continue to wear masks, stay at least 6 feet apart from others, avoid crowds, ventilate indoor spaces, and wash their hands often. These actions will help prevent the spread of COVID-19, including the new variants.

Studies suggest that antibodies generated through vaccination with the currently authorized vaccines recognize and protect against these variants. Data released from Pfizer suggest that its vaccine is highly effective against the B.1.351 variant. The company conducted a six-month study of 800 participants in South Africa. Nine members of the placebo group tested positive for COVID-19, while none of the vaccinated participants tested positive, suggesting a 100% efficacy. Pfizer is also studying the efficacy of its vaccine against other variants and additional studies are underway to determine the efficacy of other vaccine candidates against the B.1.351 and other variants as well.

Scientists are working to better understand how easily the variants might be transmitted and the effectiveness of currently authorized vaccines against them. New information about the virologic, epidemiologic, and clinical characteristics of these variants is rapidly emerging.

CDC, in collaboration with other public health agencies, is monitoring the situation closely. CDC is working to detect and characterize emerging viral variants and expand its ability to look for new COVID-19 variants. Furthermore, CDC has staff available on-the-ground support to investigate the characteristics of viral variants. For example, CDC is collaborating with EPA to confirm that disinfectants inactivate these variant viruses. As new information becomes available, CDC will provide updates.

Equitable Allocation and Distribution

The current administration recently directed all states to expand COVID-19 vaccine

eligibility to all adults by May 1, 2021. Many states are already offering vaccines

to all adults over 18 years of age.

Expanded manufacturing capabilities have increased vaccine supply in the U.S., but

it is still important to continue to build demand across the entire population.

Importantly, the public needs to trust these vaccines and be willing to get vaccinated

to make a public health impact. Building trust in the COVID-19 vaccines, particularly

in communities with a long-standing mistrust of the government is critical.

In Arkansas, currently everyone over the age of 12 is eligible to receive a COVID-19

vaccine.

Arkansas will be providing vaccines for free, but health care providers will be allowed to charge a fee for giving the shots (you do not have to pay this fee). They can recoup the fee from public and private insurance plans and from a government fund to cover uninsured individuals.

There should be zero out-of-pocket costs for individuals being vaccinated.

In Arkansas, you can visit the COVID-19 Vaccination Locations map or call 1-800-985-6030 for assistance finding a vaccine in your area or to sign up for an Arkansas Department of Health mass vaccination clinic.

You may also be eligible to receive a vaccine through your employer, through mass vaccination clinics sponsored by your local hospital system (e.g., UAMS), or through community partnerships with qualified healthcare agencies and clinics.

Not currently. Three vaccines are currently available in the U.S. under the Emergency Use Authorization– Janssen, Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna. All of them dramatically lower the risk of getting sick from COVID-19. You are likely to receive whichever vaccine is supplied to your provider/local health department by the federal government. It is important to get vaccinated when it is your turn to make sure you and your community can benefit from all of the tools we have to fight COVID-19.

The Janssen (J&J) COVID-19 vaccine is another tool to help combat COVID-19, as it has been shown to prevent severe COVID-19 illness, hospitalization, and death. The vaccine has undergone rigorous review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is now available for people who are 18 years of age and older.

Janssen’s vaccine is easier to administer than the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines

because it only requires one dose and can be stored in a regular refrigerator at doctor’s

offices, pharmacies, and other community settings. It also can be transported to mobile

vaccination sites with ease. This will greatly increase access to a critical, lifesaving

COVID-19 vaccine and get more people vaccinated as quickly as possible.

Yes, an important one. The Pfizer vaccine was actually developed in the NIH’s vaccine research center by a team of scientists led by Dr. Barney Graham and his close colleague, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett. Corbett, a Black woman, is the lead scientist for the National Institutes of Health’s coronavirus vaccine research and has addressed hesitancy within the Black community in the past. “Trust, especially when it has been stripped from people, has to be rebuilt in a brick-by-brick fashion,” Corbett said. “And so, what I say to people firstly is that I empathize, and then secondly is that I’m going to do my part in laying those bricks. And I think that if everyone on our side, as physicians and scientists, went about it that way, then the trust would start to be rebuilt.”

The Black Coalition Against COVID-19 is a trusted source of information on COVID-19 vaccine information, including through its partnership with the four historically Black medical schools in the U.S. Resources include: 1) Make it Plain: What Black America Needs to Know about COVID-19 Vaccines 2) Resources for Enrolling in Vaccine Trials, and 3) Personal account of a Black doctor who got the vaccine.

(Source: Black Coalition Against Covid-19)

The CDC has Spanish language myth-busting resources on COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and COVID-19 FAQs in Spanish.

COVIDguia.org has updated COVID-19 information in Spanish, compiled by the American Public Health

Association and the COVID-19 Latinx Task Force. PAHO has communications materials in Spanish and Portuguese for its Latin American audience.

The Department of Health for the Government of Puerto Rico maintains a Spanish-language COVID-19 vaccine website with information on the benefits of the vaccine, fact sheets, and nearly 30 FAQs, including those related to doses, concerns for pregnant women and the immunocompromised, differences between Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the need for the 3Ws even after being vaccinated, and the v-safe program.

The following sites provide key resources, updated regularly:

- AAPCHO COVID-19 Resources Page: https://www.aapcho.org/covid-19/

- Pacific Islander Covid-19 Response Team: https://picopce.org/covid19response/

The American Public Health Association provides a roundup of webinars, articles, and blogs on COVID-19 and health equity and health justice. This includes CDC data on COVID-19 racial and ethnic disparities, and information on the impact on the unhoused population.

The COVID Racial Data Tracker is a collaboration between the COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center

for Antiracist Research. It gathers the most complete and up-to-date race and ethnicity

data on COVID-19 in the U.S.

Vaccines, Pregnancy, and Lactation

A recent study was conducted involving 84 pregnant women, 31 lactating women, and 16 non-pregnant women to determine the efficacy of the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines among pregnant and lactating women. The study found that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines produced a similar immune response in pregnant and lactating women compared to non-pregnant women, and that immunity passed to newborns through placenta and breastmilk.

Animal studies of the COVID-19 vaccines before and during pregnancy have also been done and are ongoing; no evidence of harm has been shown. Despite increased regulatory issues around special populations, including people who are pregnant or lactating in clinical trials, additional studies in pregnant populations are planned. None of these vaccines contain any live virus. This means they cannot replicate and cause disease such as COVID-19.

Currently, there is no recommendation for or against COVID-19 vaccination in people who are pregnant in the U.S. This means that there is not enough information to make an official recommendation. It does not mean that the vaccines are harmful for these people, nor that their safety can be guaranteed. It means that until there is more information, agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or the World Health Organization cannot make an official recommendation to use the vaccine in special populations such as people who are pregnant.

The CDC recommends that people who are pregnant should make an individual decision with information from their medical provider about the risks or benefits of getting a vaccine while considering their risk for COVID-19. This can include their risk of being exposed to the virus, (e.g., someone who works in a health care setting versus someone who is working from home), their chance for becoming sick from the virus (e.g., someone with diabetes v. someone who has no underlying medical conditions), and what is known about the risks and benefits overall for the vaccine.

According to a recent study of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, pregnant and lactating women who receive one of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines can transfer immunity to their unborn baby through placenta and breastmilk.

Additional studies on the immune response generated by the COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant and lactating women are planned.

If people who are pregnant get COVID-19, they are at higher risk of having severe disease compared to people who are not pregnant. There is also an increased chance that they may have pre-term labor, which could affect the health of their baby.

Currently, the best science suggests that breastmilk is not likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. People may choose to continue to breastfeed with precautions (wearing a mask, washing hands) or to express breastmilk safely to use to feed their baby. Talk with your medical provider about what may be best for your health and the health of your baby if you are lactating and are diagnosed with COVID-19.

No, you do not need to take a pregnancy test before getting the COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, if you were recently vaccinated and are considering becoming pregnant, there is no recommendation to wait for any period of time after your vaccination to become pregnant.

Post-Vaccination

The three currently available vaccines make people safe from getting sick from COVID-19.

Vaccine effectiveness studies have shown that the Pfizer/BioTech and Moderna vaccines

are 90% effective after two doses once you are fully vaccinated. Real-world effectiveness

studies have not yet been completed for the Janssen vaccine. However, the clinical

trial data showed strong results, with 85% vaccine efficacy in preventing people from

getting serious COVID-19, and even stronger results against COVID-19 hospitalizations

and death.

However, while you are less at risk of getting sick from COVID-19, many people around

you are not. There are still too few people who are vaccinated. To protect others,

it is crucial to continue practicing the 3 W’s: wearing a mask, washing your hands,

and watching your distance.

CDC states that people who have been fully vaccinated (defined as those who have received the second dose of a two-dose regimen or one single-dose vaccine more than two weeks ago) can:

- Visit with other fully vaccinated people indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

- Visit with unvaccinated people from a single household indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing, as long as they are at low risk for severe illness from COVID-19

Fully vaccinated individuals are not required to quarantine after a known exposure

to COVID-19, as long as they remain asymptomatic. Fully vaccinated individuals can

also travel domestically in the U.S., as long as other protective measures are taken,

including mask wearing and social distancing.

Except for the above-mentioned activities, fully vaccinated people should continue to

wear masks and physically distance around unvaccinated people.

Evidence from a recent study conducted by CDC shows that vaccinated people are unlikely to carry or transmit the

virus that causes COVID-19 to others. However, until more people are vaccinated, it

is important for everyone to continue using all the tools available to help end the

pandemic.

According to CDC guidelines, individuals who are fully vaccinated (defined as those who have received the second dose of a two-dose regimen or one single-dose vaccine more than two weeks prior to travel) can travel domestically within the U.S. as long as they abide by other protective measures, including mask-wearing and social distancing. Fully vaccinated people do not need to get tested for COVID-19 or quarantine upon arrival when traveling domestically, as long as all other protective measures were followed. International travel is still not recommended at this time for vaccinated and unvaccinated people. However, if you are fully vaccinated and choose to travel abroad, you should follow the CDC guidance below:

- You do NOT need to get tested before leaving the U.S. unless your destination requires it

- You still need to show a negative test result or documentation of recovery from COVID-19 before boarding a flight to the U.S.

- You should still get tested three to five days after international travel

- You do not need to self-quarantine after arriving in the U.S.

Vaccinated individuals with a COVID-19 exposure are not required to quarantine if they meet all three of the following criteria:

- Are fully vaccinated, meaning it has been at least two weeks since they have received

both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of a single-dose vaccine

- Have been fully vaccinated for less than three months

- Have not experienced any COVID-19 symptoms since exposure

If you do not meet all of these criteria, then you should follow regular quarantine protocol after exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.

There is not enough evidence yet to determine how long immunity will last after vaccination. Data from Pfizer’s clinical trials show high efficacy for at least six months post-vaccination, both against mild and severe COVID-19. More research is needed to determine how long protection from the vaccine will last. Studies regarding the duration of protection for the Moderna and Janssen vaccines are ongoing.

Like other vaccines, COVID-19 vaccines can cause swollen lymph nodes in the armpit area where the shot was administered. This is a normal side effect of the vaccine and is evidence that your immune system is building protection against COVID-19.

However, swollen lymph nodes under the arm are routinely screened for during mammograms

as a potential sign of breast cancer. If you have recently been vaccinated and develop

swollen lymph nodes, it could be mistaken for breast cancer during your mammogram.

Therefore, as long as it does not delay essential medical care, you should consider

scheduling your mammogram for either before you receive the vaccine, or four to six

weeks post-vaccination.

If swelling under the arm persists for more than four to six weeks after vaccination,

consult your physician.

Information from CDC, NIH, FDA, and the Arkansas Department of Health was used to compile answers for these FAQs. If you have any further questions about COVID-19 vaccines, please contact Dr. Bryan Mader at bmader@uada.edu.

Download Important Facts about the COVID-19 Vaccines

Datos importantes sobre las vacunas de COVID-19